In earlier times, diplomats enjoying a posting to exotic Istanbul as guests of the Sublime Porte often found themselves thrown in the dungeon upon an outbreak of war between their own state and the Ottomans, and remained there for the duration of the conflict. This happened at times to French, Venetian and Russian diplomats to the horror of ‘civilized’ Europe. Back then, the Sultans did not maintain embassies abroad and did not appreciate the concept of ‘diplomatic immunity.’

Luckily for modern diplomats, the notion of legal protection for envoys and their families in the event of conflict became enshrined in the 1961 Vienna Convention.

But how did the safeguarding and repatriation of diplomats actually work in the greatest conflagration in recent history, the Second World War? Well, surprisingly, given the extent and intensity of the conflict, it worked quite well for most diplomats.

Essentially, the Second World War was divided into two arenas; first the more limited European conflict which began in 1939, and then later the widening of the war to the Far East from late 1941. In both cases, many diplomatic dependents on all sides had returned to their homelands in the months before September, as the inevitability of war gradually increased.

The European war officially started at 11.15 am on Sunday morning, 3 September 1939 when Britain’s ultimatum to Germany to withdraw from Poland expired. There was no specific declaration of war as such. The French were likewise at war with Germany when their ultimatum expired a few hours later. That same Sunday evening, the British and French diplomats in Berlin were confined to separate floors of the Adlon Hotel prior to their repatriation.

The next day, Monday 4 September, the head of the German mission to Britain, Chargé d’Affaires Dr. Kordt (the Ambassador having previously been recalled) and his remaining staff took a special train from London’s Victoria Station to Gravesend where they bordered a neutral Dutch steamer, the Batavia, for Rotterdam, travelling on from there by rail to Berlin.

On that same Monday morning, the British and French Ambassadors and their small remaining staffs in Germany also boarded special trains from Berlin for the Belgian frontier, crossing at exactly the same time as the train carrying German diplomats from Paris passed into Germany.

The British Commonwealth’s status was simplified by their foreign relations generally being dealt with by London. With the exception of Canada, which declared war formally on Germany several days later, the major Commonwealth nations were automatically at war when Britain’s ultimatum required. Generally, British diplomats handled foreign relations for the Commonwealth nations.

And so, within 48 hours of war being declared, the diplomats of the principal combatants were back in their homelands. The Swiss Embassy in London took over responsibility for the German mission premises and affairs during hostilities, and the Americans did likewise for the British and French in Berlin. All very civilised.

Two years later, in December 1941 the war widened to include Japan and the USA; the conflict had gone global. Which meant repatriation of diplomats would now be a very complicated affair.

Full credit must go to the major neutral powers at the time, the Swiss, Swedes and Portuguese for co-ordinating an incredibly complex series of exchanges involving repatriation of German and Italian diplomats from the USA, American diplomats from Europe, Japanese diplomats from Britain and the USA and Allied diplomats from Japan and Asia to Europe, the USA and Australia.

Resolving the negotiations of not only who was entitled to repatriation but also how to transport those personnel across mine and submarine infested conflict zones a world apart took a considerable amount of time, and so it was not until mid-1942 that the first exchanges were ready to proceed.

In the interim period, around 2000 German, Japanese and Italian diplomatic staff and their dependents stationed in the US along with some internees were accommodated quite comfortably at isolated mountain resorts in Virginia and West Virginia. One hundred and fifteen American diplomatic staff and dependents stationed in Berlin were moved to Jeschke’s Grand Hotel in Bad Nauheim, near Frankfurt.

First to get moving were the Germans and Italians in the US. They left New York aboard the Swedish liner Drottingholm on 7 May 1942 headed for Lisbon. After unloading them, on 22 May the Drottingholm took aboard the American diplomats from Bad Nauheim who had trained to Lisbon, and sailed back to New York, arriving on 30 May.

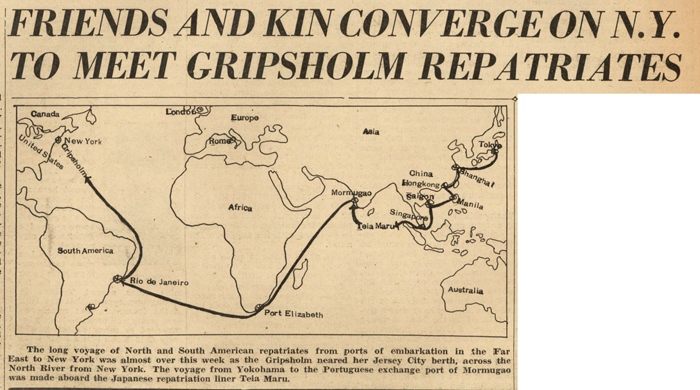

Next, in June, the Swedish liner Gripsholm picked up the Japanese Ambassador to the USA and his entourage in New York, then sailed for Rio de Janeiro where 417 more Japanese diplomats and nationals were taken aboard. Painted white with huge stripes in Sweden’s national colours fore and aft, and the words ‘Sverige,’ ‘Gripsholm’ and ‘Diplomat’ marked prominently on the hull, the vessel travelled fully lit; an anomaly in a chaos-stricken world. She steamed for neutral Portuguese Lourenco Marques (today Maputo, Mozambique) where the exchange was to take place, arriving on 22 July, after a journey of 16,000 km.

On exactly the same day, the Japanese liner Asama Maru arrived in Lourenco Marques with 800 US diplomats, dependents and nationals, including the US Ambassador to Japan, having travelled 16,000 km from Yokohama and picking up more repatriates in Hong Kong, Saigon and Singapore. With Asama Maru was the chartered Italian ship Conte Verde with 600 Allied passengers from Shanghai.

The next day, with the liners docked adjacently, 1096 Japanese passengers walked down the forward gangway of the Gripsholm and up the forward gangway of the Asama Maru, while the 1450 Americans used the stern gangplanks to depart Asama Maru and Conte Verde and enter the Gripsholm. The combined transfer took four hours. The Japanese ship left Lourenco Marques on 26 July bound for Yokohama, Japan and the Gripsholm departed two days later for New York.

Another series of exchanges occurred between Japan and Britain in July and August 1942 also at Lourenco Marques, with the Japanese ships Tatuta Maru and Kamakura Maru swapping British, Indian and Australian diplomats and dependents for Japanese equivalents aboard the SS El Nil, SS Narkurda which both headed for Liverpool, England, and the SS City of Canterbury which made for Australia.

And so, substantially all of the diplomats of the major warring nations and their dependents made it safely home, amidst the carnage and chaos, and all within a few months of declarations of war; a fairly impressive effort.

For a few diplomats however there was no happy ending. With the collapse of the Nazi regime in May 1945, the Japanese Ambassador to Germany, Hiroshi Oshima who with his staff had been stationed in Bad Gastein near Salzburg for some time to escape the bombing of Berlin, was arrested by the Allies, deported to the US and jailed until 1955 for ‘conspiring to wage aggressive war’, perhaps a rather curious charge for an ambassador, though he was a serving general in the Japanese army as well as a diplomat.

Similarly, Germany’s Ambassador to Japan, Heinrich Stahmer, was first imprisoned in Tokyo by the Japanese when Germany surrendered, and then held in jail by the Americans for another two years, after Japan surrendered. He was incarcerated for a further year in post-war Germany when he was repatriated there. Which takes us back to how the Ottomans used to treat diplomats at war.

Sources for this piece include Max Hill’s book ‘Exchange Ship’, salship.se, and Auswaertiges Amt Rundbrief article ‘The Diplomatic Exchanges’.