Often, we think of the magnificent clippers of the nineteenth century and the graceful barques of the early twentieth as the last great commercial sailing fleets to grace the wide seas. The Suez Canal and steamships put an end to the clipper era in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and the very final of the round-the-world grain races was in 1947 between Pamir and Passat from Spencer Gulf, South Australia to the UK. The efficiency of cheap and reliable marine diesel engines finally put paid to the romance, grandeur and elegance of more than thirty centuries of sail-powered trade.

In the Indian Ocean, fleets of ubiquitous Arabian dhows and boums operated solely under sail well into the 1950’s (according to Alan Villiers), as did junks in the China Seas. So, by the seventies, the fleets of long-distance timber-hulled sail-driven cargo haulers of the world had all retired; replaced by steel hulls and sooty diesels. Or had they?

Actually, no. One fleet of commercial sailing ships continued to operate without modern propulsion systems well into the 1990’s. And without the attention that such a unique development really deserved. It was a sizeable fleet too, with 800-odd ships plying to and fro under sail within living memory.

They were the pinisi-rigged praus based out of Sulawesi and Java in Indonesia, and when I dropped in to Paotere Harbour, in Makassar (then Ujung Pandang) in May of 1995, dozens of them stood loading at the wharves, still hung with sails, using the monsoons to wing them in and out of the myriad island chain that makes up the archipelago.

Of course, what had been known pre-WWII as the Dutch East Indies, made up of between 13,000 and 18,000 islands–depending on how you define such a concept–is a natural stamping ground for inter-island maritime trade, and has been for well over 2000 years.

Merchant vessels sailing through the region between India and China are noted as far back as a Chinese monk, Faxien, in AD 400, who writes of his travels on a four-masted craft that could take several hundred passengers and hundreds of tons of cargo! A very big ship, and one of many that linked ancient maritime Asia, all locally built and crewed. Such Austronesian vessels evolved over the intervening 16 centuries through numerous iterations of dimensions, hull types and sailing rigs, constantly refined and developed and improved, right down to the modern generic prahu with its signature pinisi rig.

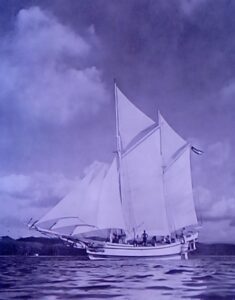

The pinisi traders of the nineties carried a distinctive seven sail ‘schooner’ rig; gaff mainsail and mizzen, each with a little triangular topsail above, and three sharp jibs on a long raked-up heavily-built bowsprit. The masts stood on timber bipods or tripods, two long quarter rudders hung on a complex stern overhang, and a huge cargo hold stood between the masts. Fore-and-aft sails such as they carried allowed pinisi to sail as close to the wind as a modern Bermuda-rigged sloop, and indeed, the schooner rig they were fitted with until the dying days of sail was derived from nineteenth century western two-masted pinnaces; hence the derived name, pinisi.

And there were graduations of size and style below the big pinisi’s and many regional variations; the Madurese leti-leti with its boomed tri-sails, the sloop-rigged Sumatran Nade, the older Prahu patorani with its tilted rectangular sails, the West Sulawesi lambo, the smaller but very fast sandeq with its outriggers, the big janggolans with their twin triangular sails, and most attractive of all (to me at least), the gorgeous, symmetrical golekan with its crab claw sails.

Though often referred to as the Bugi’s pinisi–after the itinerant sea-people of South Sulawesi who are famous for crewing them–the ships were traditionally built by the Konjo-speaking people of Sulawesi, the pinisi praus had a very unusual construction technique. Timber boats in the western world were generally built ribs first, and then the hull was planked, but pinisi and their ancestors were built plank first. To start, the long block of the keel is laid, and the hardwood planks are set off that, dowelled together with timber pegs hammered home. Plank by hammered plank, the hull grows taller, up to the waterline and then to the gunwales.

Ribs are then fitted and fixed to the planks with timber nails. The joints between planks are sealed with paperbark, tarred coir or nowadays, resin. A hull alone could be finished in a couple of months, but the fitout and rigging took several more.

Most notably in a prau’s profile, a substantial stern overhang, known as an ambeng contained the structure where the long quarter rudders were fitted, with a small low cabin forward of it. Behind the complex structure of the bowsprit, there was a foredeck, water tank and capstan, then the main mast. The main hold was decked and two-odd metres deep, with the wide flare of the hull giving it a surprisingly cavernous size. An average overall length was 25-30 metres, with a beam around a third of that. Such a vessel could haul 200 tonnes of bulk cargo–timber, household goods, flour, cement–and was easily sailed by a crew of a dozen.

The crew were mostly young men, small of stature, seemingly always happy, and wiry. They worked hard as required and demolished huge quantities of rice for each meal, mostly with fish stew. They smoked clove cigarettes, liked terrible coffee, and enjoyed playing anything remotely musical–like a metal can–on the long broad reaches under the blazing tropical sun. A trio of older men ran the boat and the crew: the skipper or nakhoda (often the owner), the bosun or malim, and the chief helmsman or kemudi. The seating position at the big rudders was designed so that a helmsman who fell asleep on the job would fall into the water; an indication of the dangers of misadventure, stranding and inattention which must have befallen many a prau.

For hundreds of years, praus traded from their Sulawesi bases according to a schedule set by the seasonal winds of the East and West monsoons. In the days when New Guinea and adjacent islands were famed for their turtle shell, birds nest, mother-of-pearl and birds of paradise, praus would take the dying winds of the west monsoon–no later than April–far to the east. By the time they arrived and loaded, the southeast trade winds were blowing through Torres Strait and they had a two thousand nautical mile ride as far as Singapore, wind astern or on the quarter all the way.

They dropped in at ports as required on the passage to sell or purchase cargo, docking their long rudders to avoid damage in the crowded anchorages. Makassar, Madura, Surabaya and Gresik were the main pinisi harbours, but the most crowded of all was always Jakarta’s Sunda Kalapa.

By September the East monsoon was dying, and it was time to return home to Sulawesi, where the ships were beached for maintenance in the off-season. And in April, the cycle started all over again, with a run to the east.

The 1990’s was the end of the road for the pinisi sailors. They lost their iconic sails to noisy Japanese diesels lumped into the hold (now known as Prau Layar Motor), with big props and driveshafts cut through the teak planks. The foremast stayed on as a derrick to lift cargo from the hold. No longer did they need to wait for the monsoon winds.

Jakarta’s Sunda Kelapa harbour today still has a collection of big timber pinisi, some old varieties that once sailed, but mostly modern versions designed around an engine. It’s a sad sight really. The graceful old ladies with their sharp bows, lashed together in a muddy creek, rotting away, some slowly settling little by little as time rolls by.

But if you look past them, out to the Java Sea, and you see the water flecked by the breeze of the monsoon, you can imagine them once again in their heyday, a half dozen sailing together, running down from the East, sails billowing with a warm wind, off to trade like the days of old.

Further reading: Adrian Horridge’s The Prau; Clifford Hawkins Praus of Indonesia; Gibson-Hill’s The Indonesian Trading boats reaching Singapore, Pierre-Yves Manguin’s The Southeast Asian Trading ship.

If you’d like to travel Indonesia on a modern pinisi, see https://www.seatrekbali.com/ or https://www.steppestravel.com/us/boats/seatrek-yachts/#

And if you’d like a new pinisi built for you: https://kastenmarine.com/phinisi_quality.htm