When I was a kid, my family moved from house to house, school to school, airbase to airbase. In the early seventies, we embarked on our most exotic posting; to Singapore. Living in Southeast Asia really brought Kipling’s Mandalay to life;

“If you’ve ‘eard the East a-callin’, you won’t never ‘eed naught else.”

No! you won’t ‘eed nothin’ else

But them spicy garlic smells,

An’ the sunshine an’ the palm-trees an’ the tinkly temple-bells;

On the road to Mandalay…

Everyone that has done a posting in Southeast Asia will know what I mean.

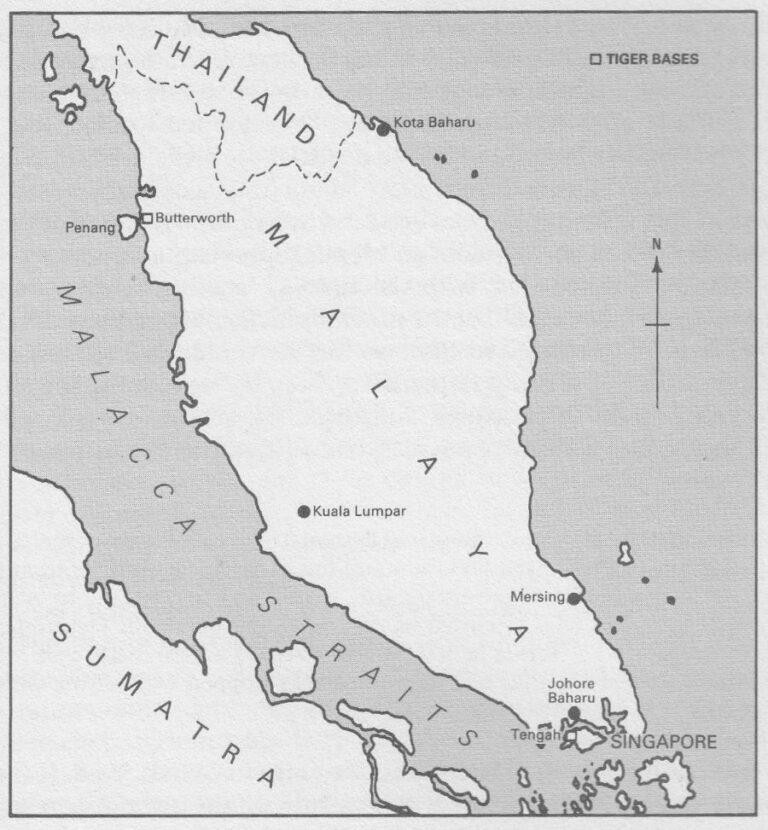

Tengah, in the west of Singapore island, was a real airbase, almost on the front line. The Confrontation with Indonesia militarily opposing the union of Malaysia and Singapore was just over. But it had been only a few years before that Indonesian paratroopers had been dropped in Malaysian Johore–just north of Singapore–and one of the Indonesian Hercules ferrying them in had crashed into the Malacca Strait trying to avoid a British Javelin fighter–flying out of Tengah–that was chasing it.

Much more serious though, was the approaching dismal end of the line in nearby South Vietnam. When Saigon fell in April 1975, a lot of battered South Vietnamese aircraft landed at Tengah, fleeing the miserable defeat. Tengah was one of a number of bases–including Butterworth at Penang, Malaysia and others operated by the US Airforce in Thailand–that formed a barrier against communism’s seemingly implacable advance through Southeast Asia.

We lived and schooled on the airbase with the sound of fast jets shaking the classroom every day, and I still recall the deafening interlude when one of the big lumbering British V-bombers took off, and the teacher stood waiting, mouth agape, at the blackboard for the roar to eventually drift away in the thick muggy air.

The RAAF at the time had just taken delivery of a very nimble French fighter, the Dassault Mirage III to replace its Sabres, and a couple of squadrons were forward-stationed at Butterworth. A detachment of those was based to the south at Tengah. They were from 75 Squadron RAAF, which had the distinction of fighting the Japanese to a standstill at Port Moresby in 1942, losing most of their Kittyhawks and pilots in the process. They later flew Mustangs, and then Vampires from Malta during the fifties.

Also at Tengah at the time was a British fighter squadron, the Tigers of 74 Squadron RAF, with a long and distinguished history at the sharp end of two world wars, and a tiger on their crest. They had started in biplanes in WWI, moved on to Spitfire’s, then Meteor jets, and now they flew the new English Electric Lightning, with the pilot sitting on top of two very powerful engines. And what do you think the young flyers from 74 and 75 squadrons talked about in the Mess at night?

Exactly correct; whose plane was fastest.

Luckily for these British and Australian pilots, there was already a template in place for answering that very question. RAF 20 Squadron flying Hawker Hunters was based at Tengah in the 1960’s, and they had often trained with and against RAAF Sabres out of Butterworth. Both aircraft were reasonably matched in terms of performance, and so the Race for the fastest time between the Tengah control tower and the Butterworth one began with these two squadrons; the fastest transit achieved was a slugish 33 minutes. When the Mirage joined the Sabre in Australian service at Butterworth in 1967, the French plane immediately set a new Race record at 24 minutes, 30 seconds. The old Hunter was just not in the same class. But soon after, a new British aircraft arrived on the scene. And it was a hot-rod.

The Lightning’s two big Rolls Royce Avons were designed to get it up to high altitude fast to intercept incoming supersonic Soviet bombers. Its turbojets put out over 32,000 pounds of raw force with afterburners lit, it could climb at 20,000 feet per minute, and it was able to attain a very respectable ceiling. One Lightning even intercepted a U-2 at 88,000 feet, which is a remarkable feat in itself. In 1984, they would go on to compete in a number of speed and speed-climb trials against F-104 Starfighters and win all, with the exception of the low-level supersonic acceleration. And the F-104 was a very fast aircraft that held a number of world speed-climb records.

The petite Mirage on the other hand had a single Atar engine giving it not quite 14,000 pounds with the burner on, and a climb rate of 16,000 feet per minute, but the French plane’s empty weight was just seven tonnes; half that of the heavy Lightning, and it had longer legs. In comparison to the temperamental Lightning–used only by the RAF and the Saudis–Dassault built over 1400 Mirage IIIs and sold them widely. Israel used them in battle with great success against contemporary Soviet fighters, like the Mig-21, and Pakistan, South Africa and Argentina also used them extensively in combat.

So, Lightning and Mirage were very different aircraft; two engines versus one, delta against swept wing, dainty contrasted to brutish, English versus French. Both were capable of flying at more than twice the speed of sound. One crucial advantage the Mirage held over the Lightning was longer range, and this would be the key in winning the Race.

The two squadrons sharing the same bases often mixed in air-to-air training; Bob Cossey in his 74 Squadron history, Tigers, describing the encounters:

“The Lightning showed considerable advantages over the French design in turns and accelerations, especially over 35,000ft, but often this could not be put to good use because of the lack of a gun, something which gave the Aussies a distinct psychological advantage…”

74 Squadron Commander, Ken Goodwin, famed as one of the best air display pilots in the history of the Lightning, put it like this in Tigers:

“In truth, the Mirage and the Lightning were fairly evenly matched. The Mirage equalled the power-to-weight ratio of the Lightning and generally had the edge in manoeuvrability. Certainly, if they had the initiative to start with they would maintain it.”

Aircraft from both squadrons regularly deployed from Singapore to Butterworth and back on what the British called ‘Tiger Rag’ runs, and quite naturally the Race records between two previous squadrons were not forgotten.

But there were a number of challenges for chasing records on this route. Firstly, 360 land miles is a long way for a fighter, especially one guzzling fuel at a prodigious rate, and you had to cross some Malay mountains over 5000 feet high. Bailing out over these mountains due to dry fuel tanks or a burning engine would also not be fun, as both the Australians and Brits had spent a decade bombing communists in the jungles along which the race route lay, so if you survived the ejection (possible) and jungle landing (unlikely), the reception on the ground was unlikely to be convivial. Thirdly, the racetrack is almost on the equator, so the thick air is heavy with moisture; lots of resistance, making you burn gas much faster. Fourth; they were combat exercises, so the planes were not necessarily ‘clean’ of pylons and possibly weapons, adding extra weight and resistance. On the other hand, there was no way you could fit drop tanks to add range, as the drag of such tanks would definitely cancel your place on the podium. And of course, fifth, pushing a high-performance machine to its limit and beyond invites the risk of your engine (or both of them if you were in a Lightning) catching fire. Messy ending. Sixth; while it was necessary to get high in the rarified air to reduce drag and hence facilitate higher speed, to finish you had to descend from high altitude for visual identification at Butterworth tower. Finally, there were complex flight profiles to consider where altitude, supersonic performance and fuel consumption needed to be traded off, and back then this was a mental exercise; there was no on-board computer to help. The Race was not an easy challenge to win.

There were of course problems blasting sonic booms all over Malaysia, and such frivolous contests could not be expected to continue indefinitely. Supersonic flying also puts tremendous stress not only on pilots but especially on airframes and engines, and the squadron engineers would no doubt soon curtail the record attempts to avoid burning out powerplants. The Lightning’s radome in the centre of its air intake also had a tendency to melt with high Mach speeds, and a radar was not cheap to replace.

Upon arrival at Tengah in 1967 with his outfit of new Lightnings, Wing Commander Goodwin immediately tried himself to uphold his squadron’s honour and snatch the Mirage’s record. Despite giving it a full afterburner take-off while trying not to watch his rapidly dropping fuel gauge, he managed Butterworth with a smidgin still in his tank but could not better the Mirage’s time.

In April, the next four plane British detachment was headed north for a ‘Tiger Run’ and its flight leader, Norman Want, was called in by Goodwin and told to regain the record and ‘put the time out of reach once and for all.’ There was no way they could lose to a damn colonial in a French plane.

It was on 18 April 1968 that Want sent his aircraft ahead individually to methodically assess speed and height versus fuel consumption; the first starting at Mach 1.3 and the two subsequent flights each dialling up the Mach numbers. The Lightning was extremely thirsty when supersonic with an intercept radius of only 150 or so miles, so it wasn’t just a question of jamming the throttles to the floor, but making sure you still had juice to land in Butterworth. His third pilot had to abandon the attempt with immolation just seconds away when his engine fire warning light came on. Back at Tengah, with calculations complete and his flight profile clear in his mind, Want (probably checked his fire extinguishers) prepared for his shot at the podium.

But there is always someone to spoil the party. Tengah’s Station Commander had got wind of what was going on, and immediately ordered Goodwin to desist. ‘Yes, Sir,’ said Goodwin and, walking Want out to his Lightning on the tarmac, told him ‘…not to worry about a thing’ and to get on with it. As Want described it:

I received a personal directive from the Station Commander as I taxied out that I was not to attempt any records. But I was having all sorts of problems with my RT that morning and got airborne and went for it. The aircraft behaved beautifully, no fire warning lights came on, and I landed with enough fuel to taxi in–and we had the record.

The new record was set at 24 minutes and 17 seconds. He’d shaved 13 seconds off the Australians. Want quickly hit Mach 1.6 climbing to 50,000 feet and then accelerated to Mach 1.99– or over 1500 miles per hour (ignoring the Lightning’s service limit of 750 miles per hour) ––at which he said, ‘…the aircraft was far from full throttle.’ In squadron lore, he left a swathe of felled trees and collapsed native huts on his path north. At that altitude, a sonic boom’s ground footprint is 50 miles wide. And there the record efforts finished; further attempts ‘rigorously’ banned by air traffic control, according to the relieved record-holding Brits of 74 Squadron.

But from the Australian side, this was not the end. It’s not clear how he managed to avoid the ‘race’ ban or what disciplinary action he subsequently faced, but in February 1971, Australian Les Dunn in a Mirage stole the record back. With all his squadron watching him and national pride at stake perhaps he just threw the rule book out the window. The Mirage could also top out at over 1500 miles (2350 kilometres) per hour so he definitely left at least one sonic boom for the rubber tappers to remember him by as he screamed above the dark jungled mountains thundering north, trying to push his throttles through the floor. Both Mirage and Lightning averaged about 900 miles per hour (780 knots) in these races, with the sound barrier at a tropical 30 degrees and a couple of thousand feet high around 780 miles per hour, and down to 660 at high altitude.

Dunn’s flight profile was also very interesting in that his flight log shows he ascended to 46,000 feet during his transit (and Want had gone up to 50,000). Hang on, why would you do that? Surely, you would stay low to cover less distance, both in the overground sense and in the vertical sense. But no, he took his Mirage up near the troposphere, and one of his squadron mates, Pete ‘Spurge’ Spurgin, explains it thus:

The main consideration would be to achieve the fastest acceleration to highest Mach No and covering max distance at the same time; this would from memory require a slight nose down bunt (approx 1/2 g) also to minimise drag, with max afterburner, causing gradual loss of height during the acceleration to Mach2+ heading towards the end point of the race.

The above was a manoeuvre during a performance test flight and the most efficient method for acceleration to Mach 2+ and in this case to maximise distance. Les obviously chose 46,000 ft as the ideal height on the day to achieve the max performance for this task. I would suggest he would have achieved Mach 2.1 at least which would have compensated for the time to 46,000 ft. Once having achieved the max Mach No, he may also have ended up at around 36,000 ft which from memory would have been the ideal mix of temp/alt/ for fuel consumption vs speed (or specific air range) in the tropics.

Remember, the Mirage only took about three minutes flat-strap to get up to 46,000 feet and it was a 24-minute race. Dunn took four seconds off Want’s record, which when you consider the speeds of both aircraft, is just a fraction of a rounding error. And it’s fair to say it is a record that will never be broken.

Any chance of regaining the title for the Royal Airforce was nullified by the sobering news that, after just four years in tropical Singapore, 74 squadron was to be disbanded and they were posted back to the UK. They had flown out with tankers from the UK, but their aircraft would now be shipped back by sea, depriving them of any last joyrides. The last ‘Tiger Rag’ flew up to Butterworth in June 1971 with the’…Australians organizing a seemingly endless stream of parties, functions and beer as their way of saying au revoir to the Tigers.’ Bob Cossey describes 74 Squadron’s very last flight over Singapore on 25 August 1971:

As a single flypast was made by four Lightnings, a General Salute was given and then, at dusk, with a glorious Singapore sunset adorning the skies and the band playing ‘Auld Lang Syne,’ a lone Lightning appeared almost silently from behind the saluting dais on reduced power as the Standard was being marched off in slow time…At the last moment [the pilot] selected 100 per cent power and pulled the Lightning into the vertical, climbing spectacularly skywards with reheat aglow in the gathering darkness.’

What a way to go out!

The Mirages of 75 Squadron at Butterworth and Tengah were deployed back to Darwin in the Northern Territory in August 1983 (Peter Condon flew his Mirage from Darwin to Butterworth in 1967 and returned it to Darwin in 1983, via Paya Lebar and Bali), later that decade upgraded to new F-18 Hornets, and are now flying the F-35 Lightning at Tindal. Pakistan happily bought 50 of the old Mirages, and still has over 80 of the type on their books, though the ex-RAAF ones were by then pretty clapped out (especially Les Dunns) and would by now be only good for spare parts.

Australian aircraft still operate regularly out of Butterworth Airbase, and it remains the only permanent RAAF base outside Australia. Tengah is now a Singaporean Airforce base; their most important and secretive one.

So why will the record never be broken? Well, firstly Singapore and Malaysia, though neighbours and members of the Five Powers Defence Agreement, are not the closest of friends, and such a ‘joy’ flight between the two countries could never, ever be mutually approved. Which airforce would be allowed to win? Plus, there is far too much civilian traffic airborne in the area now. Butterworth is a major Air Defence radar installation and politically and militarily too sensitive to draw attention to it for such a perky schoolboy prank. Also, to break the record, you’d have to go supersonic from takeoff and that’s just not allowed these days over populated areas like southern Malaysia. Too many shattered windows.

On top of that, strangely enough, fighters these days aren’t as top-end fast as they were in the 1970’s. Remember Norman Want in his Lightning hit Mach 1.99 in the Race, and Les Dunn probably made Mach 2.10. To take the record you need to be pushing Mach 2 and be able to fly 360 miles on internal fuel. In today’s Malaysian and Singaporean air forces, that deals out the RMAF Hornets (not enough speed), the RSAF F-16s (not enough speed or range), and even the RSAFs new F-35s (not enough speed). On paper, the big, twin engine RMAF Sukhoi Su-30MKM’s have the range and possibly the speed, but most of them are grounded due to maintenance problems (Russian-built) anyway. Singapore’s F-15’s would have the best chance; no problems in terms of range or speed. With one of the best power-to-weight ratios of all time and the ability to accelerate vertically, they may well steal the crown. But the Malaysians–if awake–would probably shoot them down if they came in unannounced at supersonic speed.

But good luck to anyone that takes a shot at the Mirage’s title!

Vale Les Dunn, who passed away in 2018, and to the RAF’s Ken Goodwin and Norman Want, also passed away, and cheers to all the airmen and their families who served on postings to Singapore and Malaysia during the sixties and seventies, guarding free countries from the threat of aggression. It was an interlude none of us will ever forget.

Best regards to Bob Cossey and Ian McBride from RAF 74 Squadron and Mirage pilots Dave Bowden, Peter Spurgin and Peter Condon who contributed to this piece, as well as Les Dunn’s wife Carolyn who provided his log books.

You can still see XR749, the Lightning that intercepted the U-2, at Peterhead, Scotland. And there are at least a dozen RAAF Mirages on display around various Australian sites.

For some footage of RAAF Mirages, see https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/F02782, here https://fsb.raafansw.org.au/video.php?vidID=17 great air-to-air here https://fsb.raafansw.org.au/video.php?vidID=15 For some history on Butterworth, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UxSOaFRVR_A and for some footage of Malaysian Sukhoi Su30MKM’s at Butterworth, check out https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rL2p6BTSnGE And here are more Mirages at Tengah back in the day https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XtrmfXzgdFg