Vidin is a small city on the southern bank of the Danube River in modern Bulgaria, close to the frontier with Serbia and just across the river from Romania. It is a pleasant, historic riverside city in the poorest province of Bulgaria; itself the least wealthy nation of the European Union. Highlight of Vidin is the well-preserved medieval fortress of Baba Vida.

Legend ascribes its name to a Bulgarian princess named Vida who remained unmarried and reigning at the fortress into old age. ‘Baba’ is grandma in Bulgarian, so its Granny Vida’s castle.

Due to its strategic location on the Danube and commanding bountiful agricultural plains and nearby gold mining areas, Baba Vida has a history going back over two thousand years encompassing many owners.

Recorded history notes the fortress began as a Roman auxiliary fort known as Bononia, part of the Moesian Limes that stretched along the Danube from modern Belgrade to the river’s mouth in the Black Sea. The Dacians, ruling what is now Romania, enjoyed raiding across the river into Roman Moesia, and needed to be continually punished by the Romans in return.

The Roman presence along the Danube began in the 1st century AD, during the reign of Augustus, and was strengthened following Dacian raids in AD 68/69 and 85/86. The Legion IV Scythia was based nearby and a small cavalry garrison, the First Cisipade Cohort was based at Bononia. Eventually, the problematic Dacians were subdued and the Roman province of Dacia was established north of the river, reducing the pressure on fortified settlements like Bononia. From then onwards, the length of the Danube became an important Roman trade route linking the Aegean Sea via the Black Sea and Bosporus.

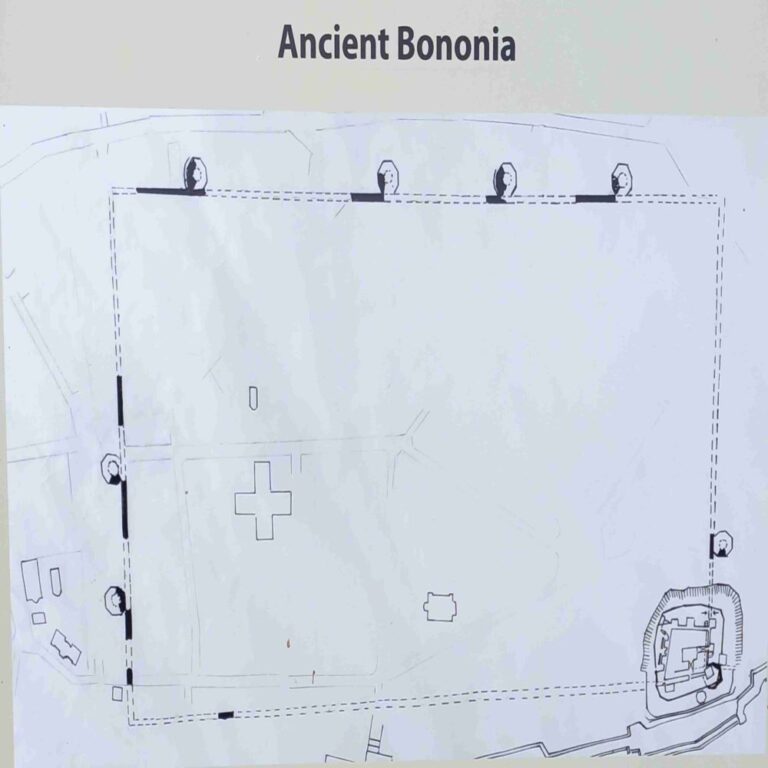

The fort at this time featured four round perimeter towers and one central pentagonal tower to a standard Roman layout. Ruins of another nearby Roman fort known as Castra Martis which also formed part of the Limes can also still be seen, with its square form cornered by four round towers. The entire system of the Danube Limes has a tentative Unesco World Heritage rating.

Bononia, part of the Moesian Limes that stretched along the Danube from modern Belgrade to the river’s mouth in the Black Sea. The Dacians, ruling what is now Romania, enjoyed raiding across the river into Roman Moesia, and needed to be continually punished by the Romans in return.

The Roman presence along the Danube began in the 1st century AD, during the reign of Augustus, and was strengthened following Dacian raids in AD 68/69 and 85/86. The Legion IV Scythia was based nearby and a small cavalry garrison, the First Cisipade Cohort was based at Bononia. Eventually, the problematic Dacians were subdued and the Roman province of Dacia was established north of the river, reducing the pressure on fortified settlements like Bononia. From then onwards, the length of the Danube became an important Roman trade route linking the Aegean Sea via the Black Sea and Bosporus.

The fort at this time featured four round perimeter towers and one central pentagonal tower to a standard Roman layout. Ruins of another nearby Roman fort known as Castra Martis which also formed part of the Limes can also still be seen, with its square form cornered by four round towers. The entire system of the Danube Limes has a tentative Unesco World Heritage rating.

In the middle of the third century Goths invaded south through Dacia, and later in the century due to their plundering the province was abandoned, and the Danube once again formed the frontier. Gradually, the Roman empire split into western (Byzantine) and eastern segments, of which the Danube frontier formed part of the latter–avoiding the fifth century Hun-induced collapse in the west. The Danube frontier forts lasted into the seventh century when invasions by Avars and Slavs devastated the area and forced the retirement of the Byzantines southwards.

Next in line to rule Vidin was the Turkic semi-nomadic Bulgars under Asparuh who initially defeated the Byzantines, and were subsequently recognised by them as an independent kingdom, known as the First Bulgarian Empire. Conflict however, between Bulgars and Byzantines continued on and off for centuries, and around the ninth century, a new stone fortress was constructed by the Bulgars incorporating some of the ruins of Roman Bononia. There were two towers; one square and one polygonal.

But the Byzantines came back, and occupied Vidin in the tenth century after a ten-month siege. Such a long siege indicates quite a well-built and powerful fortress, and one eagerly sought after. Byzantine Emperor Basil II continued campaigning, determined to eradicate the Bulgar threat once and for all. At the Battle of Kleidion in the summer of 1014, he thrashed the Bulgar army, blinding 99 of each 100 soldiers he captured–15,000 in all–which marked the end of the First Bulgarian Empire, and bequeathed Basil with the moniker ‘the Bulgar slayer’.

Most of modern Bulgaria initially remained under Byzantine rule but it later evolved as a semi-independent vassal of Constantinople later in the eleventh century. The country stands historically at a very turbulent crossroads, and invaders and conflict were never far away. The Hungarians grew more expansionist to the northwest, and the Serbs to the west. The Byzantine Empire to the south remained powerful and determined to control the lands south of the Danube. To the northeast, the ex-Mongol Golden Horde khanate’s military power was also expanding during the era, and Bulgaria was caught between all these conflicting realms.

In such a threatening environment, all rulers of Vidin modernised and rebuilt the fortress to allow it to continue to command the city and river. Inner and outer walls and a citadel were constructed, and six multi-storey square towers were added to command the curtain walls during the thirteenth century.

Vidin itself became a semi-independent state under the colourful and opportunistic Bulgarian nobleman Shishman in the thirteenth century, though he acknowledged the Bulgarian Tsars of Tarnovo, who were themselves under nominal sovereignty of the khans of the Golden Horde to the north. The fortress was captured and briefly held by the Serbs, but Shishman was reinstated as its ruler at the command of Nogai Khan, and married a Serbian princess to seal the peace. Their son, Michael Shishman reigned in the fortress for a time and was elected emperor of Bulgaria in 1323, ruling for seven years before dying in battle against the Serbs. There was never much peace in old Bulgaria.

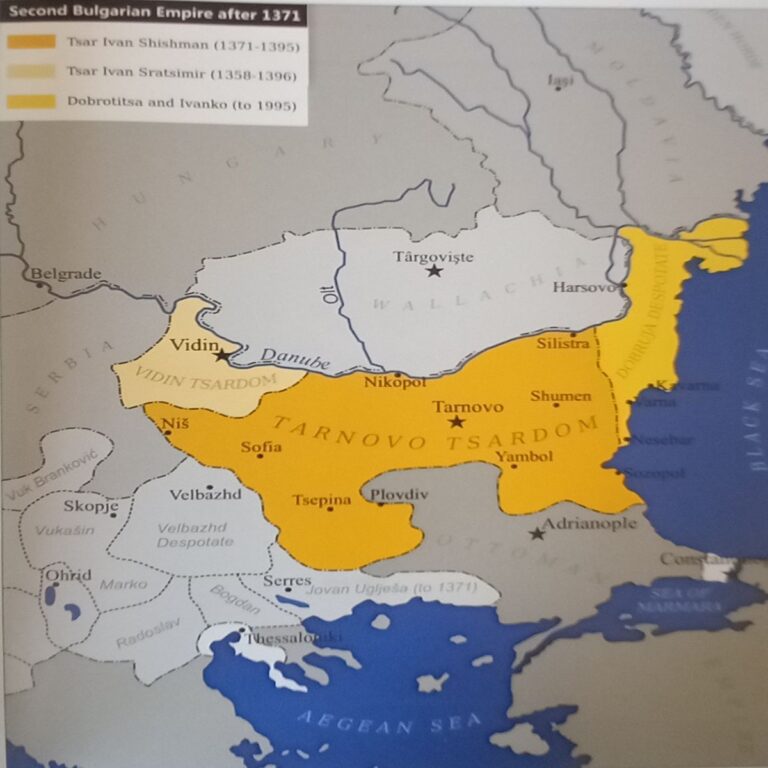

In 1356 another Bulgarian Tsar during their Second Empire created a statelet and nominated his son Ivan Sratsimir as the Tsar of Vidin, and he ruled until his lands were briefly absorbed by the Hungarians a decade later. But the Second Bulgarian Empire was running out of time by this stage.

The Ottoman Turks had grown more menacing and powerful to the southeast, and would go on to destroy the thousand-year-old Eastern Roman, or Byzantine Empire in 1453. Occupying the Balkans was a way to prevent supplies and reinforcements reaching beleaguered Constantinople. By 1380, the Bulgarians were vassals of the Ottomans, but the entire nation was overrun and absorbed soon after. Sofia fell to them in 1385, the capital Tarnovo in 1393, and–with the exception of the tiny Vidin Tsardom–the whole country had been occupied by 1396.

In September that year, a Crusading Christian army marched from Buda, Hungary to free Bulgaria and then go on to liberate the Holy Land. The vassal garrison at Vidin’s Baba Vida surrendered rather than be wiped out, and the crusaders marched on to the east. Sultan Bayezid I routed the combined armies, which included troops from the Byzantines, Croatians, Hungarians, Bulgarians, Wallachians, Poles, French, Burgundians, Germans, English, Knights Hospitaller of Rhodes, Spaniards, Italians, Bohemians, and Serbs at the crucial Battle of Nicopolis, just downstream from Vidin. It was a battle for control of eastern Europe, and the Ottomans won.

Vidin held out until conquered in 1422. It would remain in Turkish hands for nearly 500 years. As a major fortress on the dynamic and dangerous frontier between the Hapsburgs and the Ottoman Empire, the fortifications were periodically upgraded, especially to mount and withstand artillery during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. An extensive ‘Kaleto’ defensive system of strong walls encircled the entire city of Vidin, with the fortress as its lynchpin. These walls were framed by a substantial moat fed by the Danube, and pierced with five impressive entry gates at various intervals.

In 1794, Vidin’s Ottoman governor, Osman Pazvantoglu, rebelled against the sultan and declared Vidin once more independent. He expanded his borders and ruled an area from Belgrade to the Black Sea, retaining Vidin as his capital, and from behind its walls, repulsed a huge Ottoman army sent to subdue him, before burying his grievance with Constantinople and rejoining its empire.

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-8 which culminated in the independence of Bulgaria from Ottoman rule, Vidin was an important Turkish base, but distant from the main battlefront. Right at the end of the war, a Romanian force took it under siege, but hostilities ended before it could be captured.

In 1885, Baba Vida was again besieged, this time by Serbian forces during the Serbo-Bulgarian War, but its commander, Russian-trained, Bulgarian hero, Atanas Uzunov, held off the attackers until peace was signed. It was the last time the old fortress would see action.

Today Baba Vida is regarded as the best-preserved medieval fortress in Bulgaria, and a symbol of Bulgaria’s enduring presence on the Danube. While it is a mish-mash of centuries of additions, renovations and modifications and therefore not representative of any particular era, it is nevertheless a fascinating blend of styles, concepts and designs, and well worth an inspection.

The riverfront location, inner and outer walls and the multitude of surviving towers add to its allure. Large sections of the internal structures are able to be inspected, and there are some interesting though under-funded displays throughout. The footprint of the encircling semi-circular city wall throughout the city has been preserved as open space, and four impressive gates remain illustrating the cross-section of the walls. Extensive areas of perimeter walls remain intact outside the modern city.

Nearby in Vidin city are an old barracks and library from the time of Pazvantoglu some attractive restored residences from the nineteenth century, Bulgaria’s first public theatre and a newly rebuilt Synagogue. In summer, the Danube promenade is alive with cafes and cultural activities. If you are ever in the area, Baba Vida is definitely worth a look.