The loss of an extraordinary sea chart in a shipwreck in 1511 is one of the great tragedies of modern cartography.

Variously described as the ‘Javanese Map,’ or the ‘Rodrigues Map,’ this was the most comprehensive world map in existence, anywhere, when it came into the possession of Afonso Albuquerque, admiral and viceroy of the Portuguese Indies, at the time of the Portuguese capture of Malacca in 1511. Possibly it was a possession of the Malacca Sultan, who received gifts from across the Indian Ocean.

Albuquerque describes it as:

“…a large map of a Javanese pilot, containing the Cape of Good Hope, Portugal and the land of Brazil, the Red Sea and the Sea of Persia, the Clove Islands, the navigation of the Chinese and the Gores [Formosa], with their rhumbs and direct routes followed by their ships, and the hinterland, and how the kingdoms border each other. It seems to me, Sir, that this was the best thing I have ever seen…”

Albuquerque was one of the most world-wise men of his time, first voyaging to India in 1503–via Ascension Island (which he named) and Brazil, then doubling the storm-tossed southern cape of Africa before stopping at Malindi in East Africa from where he struck across the Indian Ocean to India. A return to Portugal loaded with spices followed, but in 1506 he set off again with another fleet around the Cape of Good Hope, establishing a base on Socotra, visiting Ethiopia, and capturing Muscat, Sohar and Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, before again arriving in India, to replace the existing governor.

In 1511, after a hard-fought battle, his forces captured the primary spice emporium of Asia at Malacca. While establishing that port as Portugal’s major forward base, he sent embassies to Pegu, Sumatra and Ayutthaya, planned another to China, and dispatched a squadron to finally put the legendary Spice Islands on his maps. He knew as much as any man on the planet about contemporary geography from the deck of a ship, and so if he was impressed by a map he came across in Malacca, then it must have been a remarkable example.

Why was it so remarkable?

Because no one entity had yet covered all the maritime scope illustrated on the Javanese Map. It combined the extensive existing knowledge of four then-separate maritime spheres: Portugal, with the Atlantic; the Ottoman-Arabo-Persians with the Persian Gulf, Red Sea and Arabian Sea; the Malays/Javanese with Southeast Asia; and the Chinese with the South China and East China Seas. And all in one map. It showed parts of all the major continents charted from actual quarterdeck experience for the very first time.

And, with the inclusion of ‘rhumbs’–lines, or arcs drawn on charts to allow compass courses to be followed–this was very clearly a sea chart for maritime navigation, not just generalised geographic instruments, such as Al-Idrisi’s twelfth century Tabula Rogeriana, the 1375 Catalan Atlas and the 1457 Genoese Map.

So, whose knowledge combined to make the Javanese Map?

There are several possible claimants.

The Portuguese are a certainty as a partial source. In the early sixteenth century they were entering their golden age of navigation and cartography, and they knew more of the world than any other single contemporary entity. Much of Europe still considered the Indian Ocean as a closed Ptolemaic Sea, whereas the Portuguese had sailed right through it. Navigable charts of the Baltic, North, Mediterranean, Black and Caribbean Seas were then accessible, especially to such a cartographically-focused nation as Portugal. Beyond these areas, navigable sea charts were extremely rare. Despite their official policy of map secrecy, Portugal’s discovery of Brazil was already known; appearing for example on the Cantino Planisphere in 1502. They had charted the coasts all the way from Lisbon to India by then. However, they were not familiar with navigation further east, and in 1511, were yet to sail north or east of Singapore.

The Arabo-Persians are a clear probable. The Persians first sailed east of India in the fourth to sixth centuries, and after the country was conquered in the seventh century, combined with the Arabs to maintain trade routes to East Africa, India, Southeast Asia and all the way to Canton, China. But maritime charts showing navigational routes used by Arabo-Persian sailors have not survived, though a number of confusing, contradictory and part-mythical navigational instructions by seamen such as Ibn Said (C13th), Ahmad Majiid and Sulaiman al-Mahri (both C15th) have, and these could tenuously have formed part of the basis of parts of the Javanese Map. The inclusion of coastal profiles in surviving copies of the Javanese Map also suggests some likely Persian provenance.

The Chinese are likely to have been a partial source. They had their brief moment of fame in trans-oceanic exploration in the early fifteenth century under the redoubtable Admiral Zheng He, sailing as far as East Africa and the Persian Gulf, and they were very familiar with the South China Sea, which Albuquerque made specific mention of with his reference to the ‘Gores.’ So, part of the Javanese Map could come from their knowledge, and perhaps bears some relation to the series of route maps produced for Zheng He’s expeditions, known as the Mao Kun maps (which were however lineal rather than projected representations).

A partial Ottoman source is also a possibility. The 1513 Piri Reis Map, only the westernmost segment of which survives, models the Atlantic and Caribbean on fanciful maps from Colombus, but is testament to evolving cartographic interest from the rising Turkish sultans. Even more pertinent may have been the widespread conflict between Portuguese and Ottoman squadrons in the Red and Arabian Seas and the Persian Gulf. Several Portuguese vessels were lost in battle or wrecked in the region between 1499 and 1511, and all carried a range of navigational charts for the voyage out from Portugal that may have ended up in Ottoman and then Javanese hands.

The archipelagic Malay or Nusantarian sailors are also likely to have been a significant source of data. They had ranged as far as Madagascar and the Red Sea, and north to China in the early modern era. Alone among the world’s nautical explorers, they knew where the Spice Islands were to be found (there is no pre-Portuguese record of any Arab or Chinese voyages to these islands). They were likely the source of navigational data for the Bay of Bengal–which in 1511 the Portuguese had yet to chart–and for the islands of modern Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. They had also been sailing to China for at least fifteen centuries. But, while there are several references to Malay sailor’s sea charts during the sixteenth century, tragically none have survived. There is therefore little doubt that their knowledge, and perhaps maps, must have contributed to parts of the Javanese Map.

The Nusantarian provenance of the map is also confirmed in another note from Albuquerque where he confirms it had “…names in Javanese writing” that he had translated locally, as well as apparently considerable textual data that described economic aspects such as where gold and cloves could be found within the archipelago.

What happened to the Javanese Map?

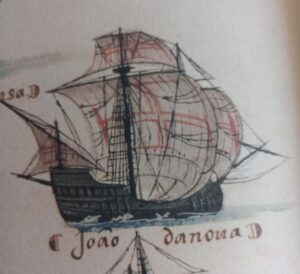

Albuquerque was so impressed with the Javanese Map, and so sure that it would be appreciated by his monarch, King Manuel, that he urgently dispatched the original after only partial or cursory copies were made in Malacca. It accompanied him on his flagship, the ill-fated Flor de la Mar in 1511 (or early 1512) headed for India, but she foundered in a squall off the Sumatra coast, and much treasure, many lives and the priceless map all went down with her in the Malacca Strait, the viceroy barely surviving the shipwreck himself.

Perhaps full copies were made, but alas, none have yet survived and surfaced, and all that remains of this amazing map is a number of sketches made by a Portuguese cartographer, Francisco Rodrigues, who accompanied the reconnaissance to the Spice Islands in 1511.

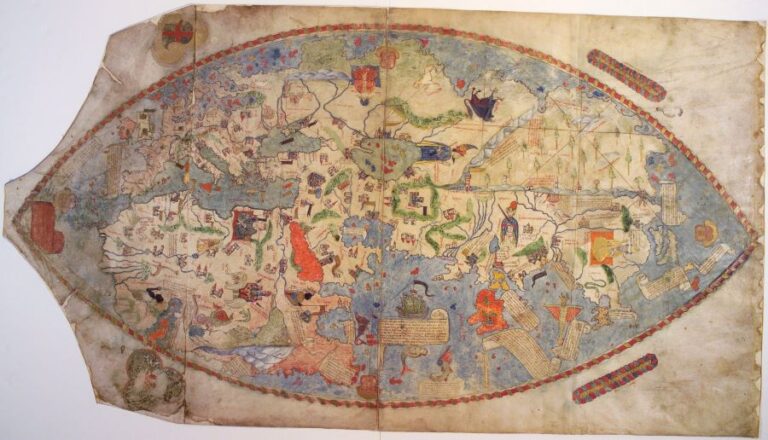

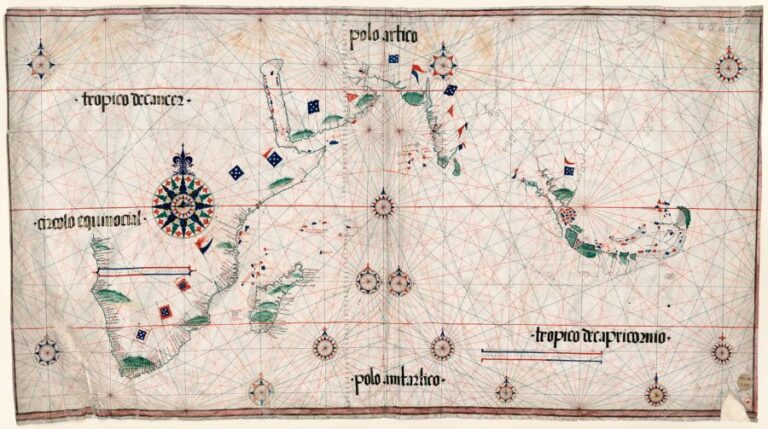

These sketches, forming an atlas, only came to light in a mis-filed nineteenth-century manuscript in Paris. Several prominent scholars have reviewed the sketch charts, including the pre-eminent Portuguese cartographic expert, Armando Cortesao. He noted that the sketch maps form a nautical atlas and consisted of two distinctive types of charts; the first series of the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, southern Africa, Ceylon all reflected current Portuguese geographic knowledge and were produced according to standard Portuguese mapping style of the time.

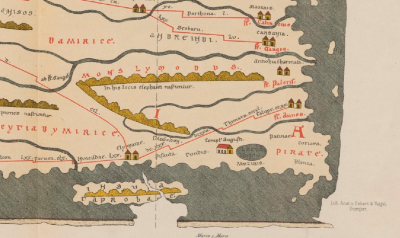

The second group consisted of charts of areas not yet charted by Europeans in 1511; the Bay of Bengal, the Malacca Strait and the arc from Java to the Moluccas and north to Canton in China. These were produced in a different style from contemporary Portuguese charts, including for example with coastal profiles–an Arabic practice, not a Portuguese one, and as such are considered to reflect elements that Rodrigues copied from the Javanese Map.

It also seems he was in a hurry to complete this sketch atlas, as many of the elements are unfinished, un-illustrated and missing toponyms. The inference is that his atlas needed to be urgently dispatched to Lisbon, and was therefore incomplete. Perhaps he worked on another version later, but it has not survived, and of course, the original map was now a victim of the sea.

What did the Javanese Map look like?

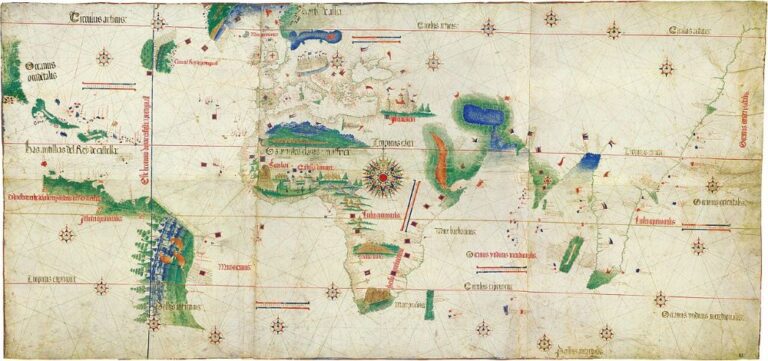

Unless a long-lost copy turns up, we can never be sure. The best guess is from Cortesao who combined and marked up Rodrigues’ charts to form a coherent map (see below). Other hints come from well-known charts that bracket 1511; namely the Cantino Planisphere and one by Pedro Reinel from around 1517. Both these maps are nautically orientated with rhumb-lines and parallels of latitude, including the equator and tropics.

Firstly, the Cantino Planisphere shows Portuguese knowledge from a decade before the Javanese Map, and would correspond roughly to the part of that map west of India, which included Portugal, Brazil and the western Indian Ocean.

The next chronological Portuguese map that depicts the East is known as Pedro Reinel’s 1517 chart, tragically also lost (thankfully copied, and to be subject of a latter Lost Maps post), but reflecting actual route charting from Francisco Rodrigues’ voyage of discovery to the Spice Islands. Unfinished coastline stretching north from the Malay peninsula does have some vague similarities to the Cortesao markup of Rodrigues’ eastern charts of c. 1515, but the vague coastline trending southeast in the top right quadrant of the chart is more reminiscent of Ptolemy than any actual landform, so it is questionable whether there is an influence from the Javanese Map.

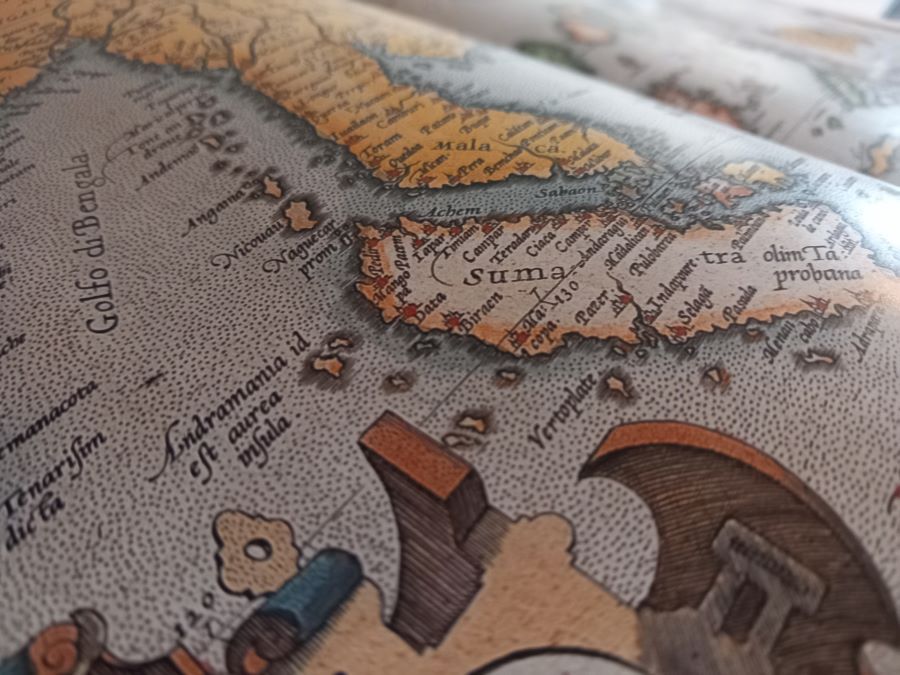

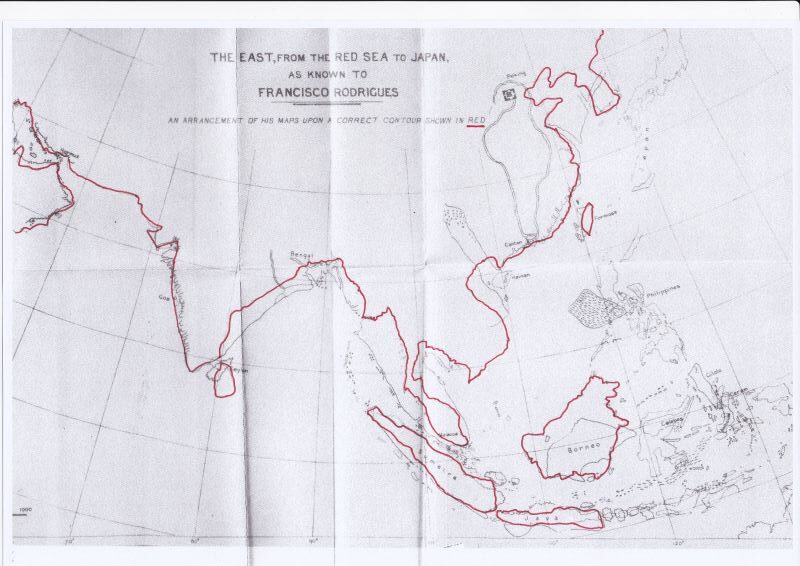

Cortesao, examined and published the Rodrigues Atlas along with the fascinating coeval description of the Indies by Tome Pires, Suma Oriental. He laboriously compiled, adjusted and combined the eastern parts of Rodrigues’ charts and aligned a modern map for comparison.

This representation is shown above, and probably gives us the best understanding of how the east of the Javanese Map looked to Albuquerque. If you can summon your imagination to combine this with the western portion of the Cantino Planisphere, and combine them so they stretch from the Caribbean to China, add hundreds of ports, cities, harbours, navigational hazards, route markings and details about what products were traded from prominent locations, perhaps you come up with an image of what amazed Albuquerque back in 1511, and why the loss of this, the most advanced map in the world at the time, was such a horrible tragedy.