Constantinople’s land walls had a fearsome reputation in the ancient and medieval worlds. Centuries before they were described as the strongest bastions in Christendom, they had repulsed army after army down through the ages. For more than a thousand years they protected the great city on the Bosporus; the greatest bastion of Christendom.

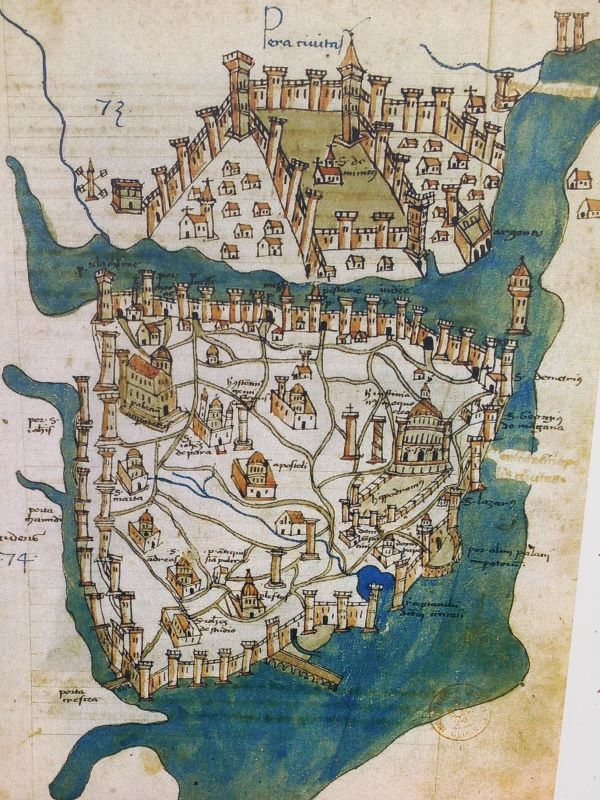

Constantinople, initially known as Byzantion, was founded in 667 BC by wandering Greek settlers, its prime location dominating the Bosporus–which provided access to the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara, which led south to the Dardanelles and then the Mediterranean. The Bosporus then, as now, was a crucial maritime trade route linking the shores of the adjacent seas and bridging the narrow gap between the Asian shore of Anatolia and the European one of Thrace.

The earliest city walls covered just the first of the seven hills that later made up the capital of the Byzantine Empire. This corresponds to the elevation on which Hagia Sophia stands. The city first fell to invaders when Persian emperor Darius I built a pontoon bridge nearby across the Bosporus to march west and punish the Scythians along the Danube around 500 BC. Eventually, the Greeks rebelled against the occupiers, and the city was then destroyed by the Persians in revenge.

But it was too strategic a location to stay a ruin for long, and now it was time for wars among the Greek city-states, who sided with either Athens or Sparta in an endless series of campaigns. Byzantion surrendered to an Athenian blockade, then a Spartan counterattack, and was later seized in an Athenian coup. When the Macedonians under Phillip I laid siege to the city–at that time containing around 20,000 people–its land walls were already formidable, and held him off for a whole year. It was a rare defeat for Phillip.

Perhaps that is why his son, Alexander (soon to become ‘the Great’) crossed into Asia at the Dardanelles, rather than the Bosporus, ignoring Byzantion on his long march to India. Stability under Macedonian rule allowed trade and commerce to flourish, and the city developed a reputation as a democratic, hedonistic, well-defended commercial hub. Rampaging Gauls looked at the walls in 279 BC, and marched on. Rhodes and Bythnia soon attacked unsuccessfully by sea, also deterred by the great land bastions.

Then came the Romans. Around 200 BC Rome occupied roughly the Italian peninsular. Two hundred years later, they had encircled the Mediterranean. Thriving Byzantion enjoyed a period of prosperity under Roman rule, but it was still relatively small; the main gate through the walls stood then where the Bascillica Cisterns are now found. But stability never lasted long in this tough neighbourhood. The city got caught up in the Roman civil wars, often had to pick sides, and sometimes picked the loser’s side. After a three-year siege in 195 AD, the city surrendered, its inhabitants were killed or enslaved, and the great walls were torn down.

But again, it was too good a spot to stay empty for long. The Romans themselves rebuilt it, and the walls went back up, further west of the old ones. These were known as the Severan Walls, but they weren’t enough to hold off the plundering Goths in 267 AD. Byzantion was torched once more. Yet again rebuilt it would be the last time the land walls were breached for nearly 1200 years. That is a very impressive record for such a contested city.

The empire of Rome was on its last legs by the third century, but the eastern Christian empire of Constantine, with his capital at what he christened ‘Nova Roma,’ but what posterity knows as Constantinople–the city of Constantine–was just beginning. And, as a sign of his grand plans for the city, he built a new set of great land walls three kilometres west of the Severan Walls, expanding the city footprint by a factor of four.

The bustling city at this time–home to around 300,000 people–was filled with fine public buildings, churches, markets, forums, bath-complexes, palaces, and of course, the chariot racetrack Hippodrome. The Wall of Constantine were completed in the mid-fourth century and formed a single structure, studded with defensive towers and at least five gates, and while we know its rough route, no significant trace remains. The earlier Severan Walls are also lost to history.

Rampaging Visigoths, Vandals and Sassanians in the first half of the fifth century led to the next improvements in the defences, with Emperor Theodosius II overseeing construction of a new set of walls around two kilometres west of Constantine’s Walls. These Theodosian Walls were eventually the ultimate pre-gunpowder system of defensive fortifications: the strongest fortifications in Christendom.

The main wall reached up around 13 metres and was nearly five thick, faced with cut limestone, and banded with mortared brickwork giving it the distinctive appearance that is visible even today. Ninety-six towers stood up to 20 metres above the wall and projected ten metres proud of it, and were no further than 50 metres apart.

After a series of earthquakes caused extensive damage–one in 447 destroying 57 towers–repairs were carried out and a further, lower outer wall was added to the system. This new wall at around 7 metres high was dominated by the taller ‘inner’ wall and intended to prevent escalade of the main wall and protect its base. This new wall too, was heavily provided with a lower series of towers at intervals. Later still, a further lower scarp wall two metres high was constructed outside the outer wall dominating a water-filled moat 18 metres wide and six or seven deep. A terrace around 18 metres wide stood between inner and outer walls, and a lower terrace 12 metres wide, between the scarp and outer walls.

So, to surmount the defences and start plundering, you needed to first cross a wide, deep moat; from the moat immediately scale a wall taller than a man; cross an open space under fire from both inner walls; mount a seven-metre wall dominated by towers twice as high as the ramparts; somehow climb down that structure–there was no external access– and from there contemplate how you would get atop the last, inner wall 20 metres high which had ballistae, catapults, crossbows and arquebuses firing at you from its ramparts. Properly manned and before cannon and gunpowder, scaling these walls was not an inviting proposition for most armies.

A few gave it a try–Bulgars, Avars, Arabs, Russians and Turks–but without success. Between the Goths in 267 and the Turks in 1453, the city fell just once, to the French and Venetian scum of the Fourth Crusade in 1204. Diverting from a papal-sanctioned plan to retake the Holy Land, these crusaders were instead conned by the promise of plunder to attack the great imperial capital, and with their large fleet and the rulers of Constantinople in disarray, they stormed the walls and held the city for sixty odd years. But, with the aid of their fleet, they scaled the less sophisticated sea walls in the Golden Horn, rather than the formidable land walls barring the peninsula to attackers.

While the Byzantine Empire was restored, the loss of most of its territory, the plundering of its treasury, the reduction of its population–from a peak of around 800,000 to just 70,000 in the fifteenth century–and the demise of its once great army all signified its terminal decline. Constantinople’s heyday and pinnacle of wealth was in the twelfth century. The Fourth Crusade dealt the empire its death knell, but it would not finally succumb for two and a half centuries.

The rise of the Ottomans from the fourteenth century mirrored the decline of the Byzantines. Constantinople was high on their list. They attacked in 1391, 1396, 1411 and again in 1422. Each time they were driven off by the great land walls, despite the withered state of available Byzantine defenders.

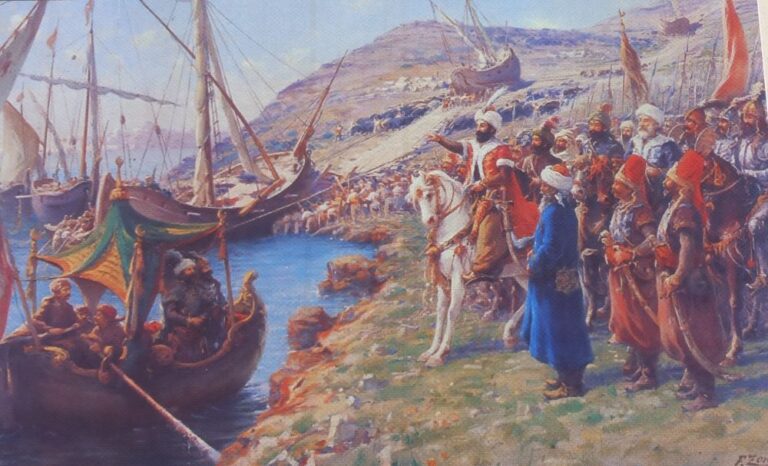

Finally, in April 1453, Sultan Mehmed II, arrived to lay siege, seeking success where all others had failed. And he went about the process methodically. Earlier, he had built a fortress on the Bosporus just north of Constantinople to match an existing one on the Asian side. These, nicknamed the ‘throat-cutters,’ stopped trade and support reaching the capital from the north. His fleet sat off the city, preventing reinforcement, and his army–perhaps 80,000 strong–landed to surround the land walls. There were only 7000 defenders to cover the six kilometres of land walls and the thirteen of sea-walls. The great iron chain that blocked access to the Golden Horn, was outflanked when the Turks dragged galleys across the narrow neck of Galata.

But the game-changer the sultan had brought along was his great siege cannons–several dozen of them. Never before had such a weight of firepower been directed at medieval walls by gunpowder weapons. Old castle walls were tall and narrow to make it difficult to escalade, but in the nascent age of artillery, their height made them easy targets, and their slender width made a sustained bombardment catastrophic for them.

Despite all this firepower, these early cannon were temperamental beasts. They often exploded, killing their crews; they took several hours to reload; they were inaccurate; there was a shortage of cannonballs, as the biggest of these guns threw an incredible 280-kilogram ball; and the besieged repaired the damage like their lives depended on it. As indeed it did. The massive triple wall system had caused problems for the gunners, and underground mining and massed infantry assaults were needed to complement the barrage.

After nearly two months of constant battering, several breaches had been blasted in the outer wall. The weakest point of the entire land walls was the valley of the Lycus River, between the city’s sixth and seventh hills, near the Fifth Military Gate. This valley was commanded from above on both sides, and it was opposite here the sultan had sent up his tent to watch the show.

His men attacked the shattered walls in the early hours of 29th May. The sultan kept sending wave after wave to be mown down, until the last wave of his best troops finally over-powered the outnumbered and exhausted defenders. The last Roman emperor took up his sword and died with his troops. The Ottomans embarked on a three-day sack of plunder, rape, slaughter and pillage, enslaving the last survivors.

The victorious sultan–just twenty-one years old–entered the shattered city later that day, via the Charisius Gate, and proceeded, supposedly shocked at the destruction, to the church of Hagia Sophia. It was converted to a mosque and he said his thanks to his god. He had earned the eternal sobriquet ‘conqueror’.

On a recent visit to Istanbul, I walked the full length of the Theodosian Walls from the fortress of Yedukule Fortress on the Sea of Marmara to the Golden Horn (about 6 kilometres), and was pleasantly surprised to see how much remained of the roughly 1600-year-old structure. Some sections are ruined, and some encroached by urban development, other stretches are renovated or being refurbished, but there is a rewarding quantity that you can inspect by walking the great old walls, from the inside or outside. Its worth a look if you get the chance.

A great book to read is ‘Constantinople: The Last Great Siege 1453‘ by Roger Crowley, and an excellent website that helps to decipher the numerous visible inscriptions on the walls is here.