Once in a generation, or even in a lifetime, a spectacular archaeological discovery changes our whole view of a part of world history. Think of structures, like Raffles location of Borobudur in 1814 or Bingham’s find of Machu Pichu in 1911; or of instruments like Napoleon’s soldiers unearthing the Rosetta Stone, or a shepherd stumbling on the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947.

Marine archaeology has had some amazing moments too. Like finding and raising the incredible Swedish Vasa from 1628 or the Mary Rose from 1545, lost shipwrecks that opened our eyes to those eras; both of which–painstakingly restored–can be marvelled at today.

In 1998, some Indonesian fishermen diving for sea cucumber came across a wreck over a thousand years old, the Belitung Wreck, and it changed our understanding of the sea trade before the turn of the first millennium, in the waters of Southeast Asia. The wreck was astonishing on two accounts; the incredible cargo, and the construction style of the ship itself.

Luckily, before plunderers arrived, marine archaeologists became involved, and over two seasons in the late 1990s, the wreck was excavated and its cargo recovered. Most of the hull had rotted away over the intervening twelve centuries, but enough remained to develop an understanding of the unique construction techniques, and the placement of the load of Tang Dynasty porcelain–all 60,000 pieces– gave an idea of the hull layout and dimensions.

And from these scanty details, an extraordinary replica was funded and built, in the same ancient style as the wreck, and she subsequently sailed from the Middle East to Singapore, along the path of her ancestor, and through the same monsoon-swept seas. More on the replica later.

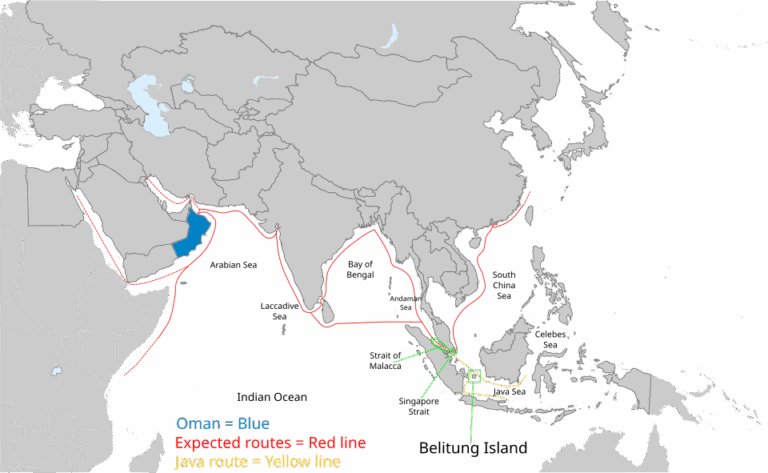

The original ship came to grief three kilometres off the Java Sea island of Belitung–which lies between Sumatra and Borneo–appearing to clip a reef which opened her hull and sent her to the bottom to lie undiscovered for more than a thousand years. As there are some decent landmarks for coastal navigation nearby, 660 metre Bui on nearby Bangka, and 500 metre Tajam on Belitung itself, our unlucky vessel may have hit the coral at night or in inclement weather probably while trying to make it to nearby Palembang.

Palembang was the capital of the empire of Srivijaya for over six hundred years, and trade routes radiated out from the Musi River on which she stood; west through the Malacca Strait to India and the glittering cities of the Arabic Caliphate, north to China, and east where the trinity of priceless spices, nutmeg, cloves and sandalwood hailed from.

Loaded with Chinese porcelain, the ship had no doubt sailed down through the South China Sea, most likely after loading up at Guangzhou (previously Canton, and known to the Arabs as Khanfu), which was the principal harbour for foreign traders in China in the late ninth century. Sources note over 200,000 foreigners resident there at that time. It was common for such traders to sail on the north-easterly winter monsoon which crept down the China coast by October or so. They would perhaps stop off at harbours on the Indochina coast to avoid the Spratly and Paracel reefs, and then generally turn north after passing Singapore, into the Malacca Strait, and onwards across the Indian Ocean. But this ship continued to sail south, most likely heading to Palembang or maybe a Javan port, perhaps to top up with spices unavailable in China. And the path south held many dangers, with hazards spread like nets across its route.

First a ship had to negotiate the way through the scatter of the Riau Islands between Malaysia and Borneo, and then the reef and sandbar-strewn passage west of Bangka, or the even more hazardous Gaspar Strait between Bangka and Belitung Islands. Postcard-pretty golden islands girt by coral reefs lie scattered across these tropical seas, waiting for tired crews never quite sure exactly where they were. It seems our unlucky ship was off-course in the Gaspar Strait, a little too far east, when she met her doom.

Based on the keel and some other structural elements, the hull was 18 metres long and six wide, which is quite small considering it carried 25 tonnes of crockery. Analysis of the ships timber indicate an East African origin–common for Arabo-Persian ships where good maritime wood is lacking. But it was the method of joining the hull planks that was most fascinating, because they were sewn together; no nails were used in the vessel at all. This style of construction is distinctly focused on the Persian Gulf, and had often been considered as too weak for the often heavy weather of the South China Sea, but here it was in Southeast Asia after a voyage from China!

Most likely, she was headed ultimately for Siraf, in modern Iran, at the time the major western terminus for the China trade. Which makes the return voyage an incredible 11,000 nautical mile odyssey. Very much like the tales of old Sinbad, who sailed those very waters in his fables.

The cargo spent six years being conserved by the best experts in the business, and was then purchased by the Singapore government for USD $32 million. That’s what a shipwreck of Tang porcelain is worth these days–and why the few that are discovered generally get pillaged before the archaeologists get near. After a globe-trotting series of exhibitions, it is now on display at the Singapore Asian Civilisations Museum, and well worth a look. Mostly it consists of painted bowls from the Changsa kilns of Hunan, with smaller quantities of green-glazed Yue ware from Zhejiang, white-glazed stoneware from Hebei, impressive green-splashed items from Gongxian, all packed in large storage jars from Guangzhou. The industrial scale of the trade is clearly apparent, and further highlighted by some of the ceramics already being produced with Islamic motifs for their target market. It is easily the largest hoard of Tang ceramics ever recovered from a shipwreck.

A number of non-ceramic items were also found including silver ingots, copper coins, a stunning Tang gold cup, and possessions of the crew. Gambler’s dice, fishing sinkers, a sailmakers needle and a cook’s mortar and pestle give us a glimpse of a sailors life in the ninth century. Distinctly Chinese bronze spoons, jewellery, and an ink set suggest affluent Chinese passengers may have been aboard. And as no human remains were found, it seems to provide some hope that those aboard made it to land after striking the reef.

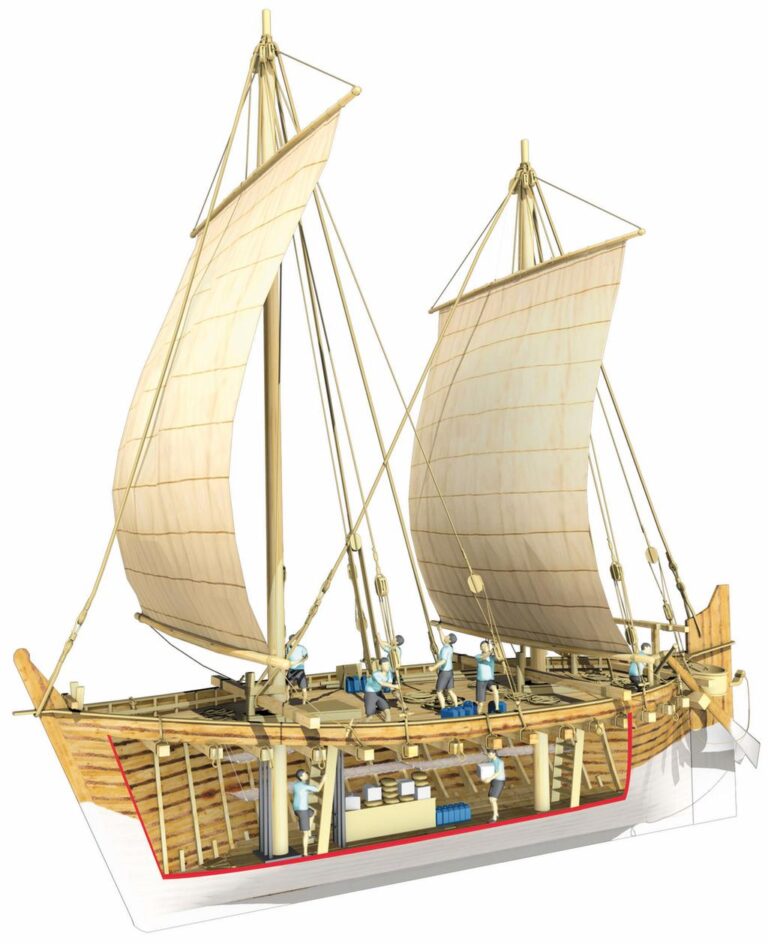

The next phase of this tale is the best. The government of Oman funded a full-size replica, based on the wreck, and Singapore financed the voyage from Oman along the ancient maritime Silk Road to the island state.

A team, including maritime archaeologists Tom Vosmer and Nick Burningham, produced a design based on analysis of the shipwreck, and it was built on a beach in Oman, in the traditional style, from a mix of African hardwood, teak, juniper and palmwood. Fairly uniquely, the hull was built shell first and later framed. This was necessary because the builders followed the traditional style, and each hull plank had to be sewn to the one adjacent. This extremely time-consuming method required the drilling of 37,000 holes for the fibre to be stitched, and 120 kilometres of coconut cordage to seal the gap between planks and the holes themselves after the cordage was stitched through!

As the hull took shape, much of the sailing rig had to be designed by guesswork. None of the elements had survived the long immersion. Two masts were decided upon to spread the sail load, square sails were fitted–lateens that were thought to have equipped Arab ships for centuries have now been found to have been a recent development–clad with canvas, spars were shaped in teak and all rigging was either manila or coconut fibre. A steering system of two quarter and one median rudder was fitted, crew gathered, and on 10 February 2010, the head-turning dhow, christened Jewel of Muscat, set out from Oman, first for India, then on to Singapore. But that voyage is another story…Coming soon.