Run for Manhattan

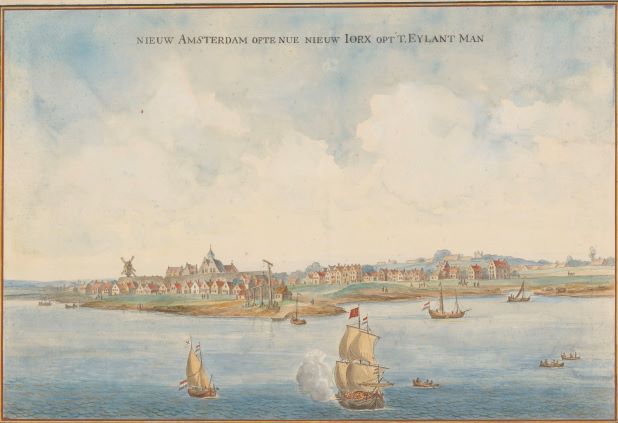

New Amsterdam, Manhattan Island c. 1665

The seventeenth century. Two islands. On different sides of the world. One a few miles from the equator, the other almost halfway from there to the North Pole. The Pacific Ocean and North America lay between them.

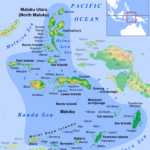

One island was Manhattan, but by far the most important was Run Island. One of the Banda Islands group in the far east of the East Indies (now Indonesia), Run was the western most speck–you can walk around it in a couple of hours–of a tiny archipelago far off the trade routes.

But on Run and across the other nine Banda Islands, and only on them came one of the most precious spices on the planet. For the Banda’s were the only place where nutmeg trees grew. And for more than a thousand years, nutmeg has been eagerly sought from Hamburg to Hormuz to Hainan as a sweetener, an additive a medicine and a cosmetic.

Nutmeg is the powdered stone of the nutmeg fruit, and that stone is encased by an even more valuable surrounding skin, known as mace. What spurred on the sixteenth and seventeenth century Age of Discovery was enterprising Portuguese finding the incredibly remote source of the nutmeg and mace, and soon after, of the cloves–which grew only in the Moluccas a week’s sail to the north. They traded cloth from India for shiploads of these spices and when they were sold back in Europe, what had been swapped at Banda for a copper coin worth of fabric got them 350 of the same copper coins; an incredible profit (mostly for the king)!!

The Portuguese were content to send a ship or two each year to cram their holds, but around 1600 the Dutch arrived with much greater ambitions; they decided to corner the entire nutmeg market and conquer all the Bandas.

The Dutch East Indies company (known as the VOC) built their first fort, Fort Nassau on Banda in 1609. Ten thousand miles away, that same year, an English explorer engaged by the Dutch gave his name to the Hudson River and noted Manhattan Island as he sailed up the river to Albany. Not far to the north, French traders were settling in to Quebec.

Back in the Indies, England too, had smelt the spice profits that could be had, but they were slower than the Dutch in mobilising. Francis Drake had visited the Moluccas on his circumnavigation in 1580, returning with a ship-load of cloves, but his countrymen were slow to follow up and their traders in the spice race were beaten by the Dutch. By the time the English arrived nearly all the good Spice Islands had been snapped up by the VOC, the Portuguese and the Spanish. Some islands, like Ternate in the clove Moluccas, had forts from both sides on the one tiny landmass.

To secure the nutmeg, the Dutch fought a bitter campaign against the Bandanese people, virtually wiping out many communities. In 1616, they conquered Ai Island after a lengthy campaign that cost most of local people their lives. It was the second last of the Bandas to fall to them.

In all the Spice Islands now, there was just one island left not occupied; the isle of Run, outer neighbour of Ai.

Holland’s governor general in the East Indies at the time was the driven and ruthless Jan Coen. It was he who had pacified the Bandanese. There was just one pesky English base in the Bandas left to destroy before he could turn his attention north to the Iberians in the clove islands. The base on Run.

That base was commanded by an irrepressible Englishman, Nathaniel Courthope (for more on him, read Giles Milton’s Nathaniel’s Nutmeg). He had arrived with two ships late in 1616, quickly convinced the embattled local chiefs to sign a treaty with King James and built a couple of small forts for defence. But Courthope was never adequately supported by his countrymen, Dutch seapower was much stronger than English and keeping Ai supplied–it had no fresh water–was always challenging. He lost one ship, then a second.

In the same year and far away, a Dutch expedition sailed past Manhattan and built another Fort Nassau far up the Hudson River near Albany (now capital of New York State) as a trade post. Beaver pelts were all the rage in Europe, and Indian tribes traded furs for knives, whiskey and guns at such posts.

After four hard, lean years on Run, in 1620 on a night resupply run Courthope was intercepted by the Dutch and disappeared. The forlorn garrison on Run submitted to the might of the VOC, England’s flag was lowered and her little forts demolished. The Dutch finally had their nutmeg islands.

Back to North America, and a few years later, after drifting between a number of temporary trading posts, the nascent Dutch colony of New Amsterdam built Fort Amsterdam on Manhattan Island as a fur trading station. It was a time of widespread conflict as English, French and Dutch-backed tribes clashed over territory–a story told well in the book and movie Last of the Mohicans.

In the Bandas, victory over the English didn’t bring the rewards the Dutch anticipated. Firstly, they had killed off most of the locals that knew about harvesting the delicate nutmeg trees. Secondly, they faced regular local rebellions across all the East Indies and they were still toe-to-toe with the Spanish in the northern clove islands. And finally, the lack of success in the Spice Islands bade the English to look for new commercial opportunities, and these they found in India which had much, much more potential. The Spice Islands were becoming a backwater.

England and Holland were proud, spirited commercial competitors with possessions from North America to Africa to the Pacific, and inevitably they came to blows. Both had large fleets, and in 1652, two of these went head-to-head, igniting a larger war that continued for two years. The underlying issues were never really settled. On the Atlantic coast of North America, the Swedes and English settlements had boxed in New Amsterdam, and in 1664, an English squadron took it over.

Another war followed, the Second Anglo-Dutch War (there were six all up), with conflict mostly in the Channel and the Caribbean. Peace came in the way of pedantic contemporary negotiations with the 1667 Treaty of Breda. Negotiations for the Treaty had dragged on between the Dutch and English for months. A humiliating Dutch raid up the Thames where they captured the Royal Navy’s flagship encouraged King Charles II to soften his negotiating stance, and the agreement was signed on the last day of July. There had been a great deal to sort out. English treaties with Denmark and France followed the one with the Dutch republic. All other European powers watched on very closely. Territories from Africa’s Gold Coast to Surinam, the Caribbean and North America had been up for grabs.

One of the main legal principles of the treaty had been the concept of Uti possidetis, or roughly, you hold it, you keep it. And so, with the English in possession of New Amsterdam–now named New York–and the Dutch holding Run Island, the status quo was maintained, with each party abandoning their previous claims. In other words, Run was swapped for Manhattan.

Observers looked at the relative value and scarcity of nutmeg compared with a swampy fur trading post afflicted by warring Indian tribes and mosquitos, and saw the Dutch as having got the better of the deal.

Today, everyone knows about Manhattan, but few have heard of Run, let alone set foot on it. But if you get the chance to gaze out from its lush tropical fringe across turquoise waters and coral reefs, it’s amazing to consider that once, the potential of Run and its nutmeg crop was so great that empires clashed and many died for the chance to hold onto its reef-fringed forested hills, and the sweet, pungent powder of its nutmeg trees.

Run for Manhattan. Who would have thought?