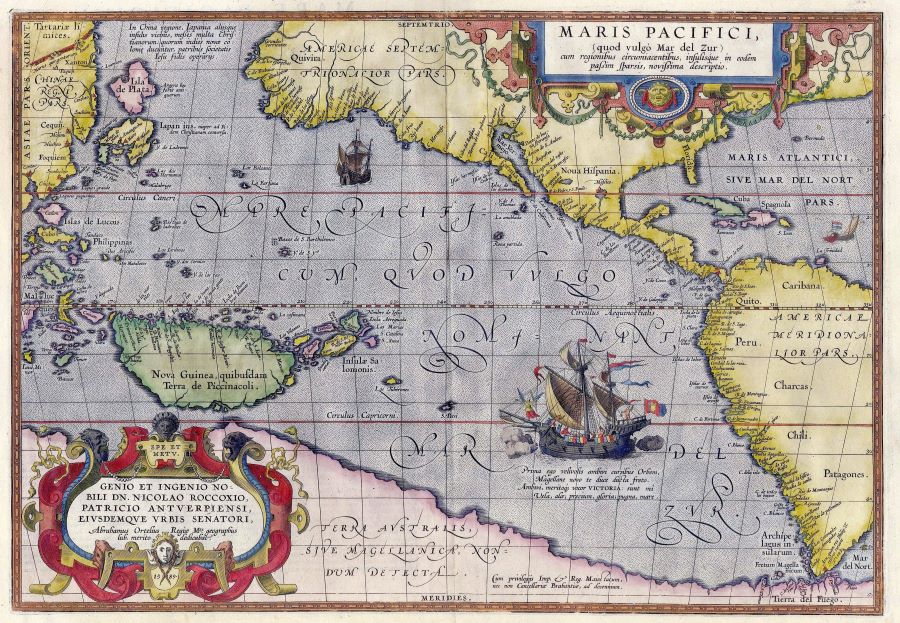

Maris Pacifici, the first printed map to portray the entirety of the Pacific Ocean was engraved by Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius in 1589 and reflects both impressive evolving knowledge, curious irregularities and the perpetuation of some ancient myths. Ortelius, also famous for producing the first world atlas Theatre of the World in 1570, was one of the stars of the Dutch Golden Age of cartography.

While Ferdinand Magellan was first to describe the ocean as ‘pacific,’ it was nearly two decades after the return of the Victoria, sole circumnavigator of the expedition, that German academic Sebastian Munster was first to apply the name to a re-jigged world map from classical geographer Ptolemy, and the title then stuck. So, from 1540, we have the Pacific Ocean.

The hand-coloured map shows a stretch of the globe, in the east from the Magellan Strait north to the latitude of New York, and in the west from China and Tartaria southward past the Spice Islands to the mythical Terra Australis–the South Land. In Ortelius’ depiction we can identify Florida, the Caribbean, Panama, California, New Guinea, a rather warped Japan, the China coast, the Philippines and of course, the Spice Islands themselves. All of these locations had been explored to some degree by this stage of the Age of Discovery either by the Spanish or the Portuguese.

In fact, apart from those nation’s explorers, only two non-Iberian expeditions had, by the time of Maris Pacifici’s printing, sailed the Pacific; Englishmen Drake (1578) and Cavendish (1587). The first Dutch expedition to see the ocean would not round South America until 1599.

On the shores of the great ocean, by the time Ortelius etched his map, the Portuguese already had settlements or trade posts at Macau in China, Nagasaki in Japan, Ambon, Banda and Tidore in the Spice Islands, and on Timor. The Spanish had posts in the Philippines, on Guam, and at Panama, Mexico, Peru and Chile in the Americas. Taking that into consideration, it seems likely that Ortelius gained most of his inputs for Maris Pacifici from Spanish rather than Portuguese sources. Note that Portuguese Brazil is deliberately excluded from the map in the east, and Malacca and Goa are not in picture in the west.

Of course, the Iberians knew much more in 1589 than is shown on this map. Piratical plundering by Drake and Cavendish on their Pacific voyages–the latter the first to ever capture a loaded Manilla Galleon–had alerted the Spanish empire to its vulnerabilities from attacks around South America, and they had no intention to send an invitation to other interlopers by providing decent charts to mapmakers like Ortelius. In any case, Maris Pacifici is most certainly not a navigators chart, but a comment on evolving geography.

Interestingly, this map provides not only the equator–with a graduated scale–and the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, but a grid of latitude and longitude. If you look closely, you can see that the meridians of longitude diminish in width with distance away from the equator, providing us with a more meaningful method of depicting a spherical earth on a flat page. This is an early Mercator Projection, for Gerardus Mercator who pioneered this solution was a friend of Ortelius, and also Flemish. Such concepts of grids and projections were established by 2nd century AD Greek geographer Ptolemy, but needed to be relearnt by most after the intervening thousand-odd years of Europe’s Dark Ages.

Of course, while calculating latitude could be accomplished by means of solar or astronomical observations, accurately determining longitude from a ship’s deck was difficult before the advent of marine timepieces (which did not arrive until the late C18th). And that is one aspect where the problems with this map lie. The Pacific is, quite obviously far too narrow. There are just not enough meridians of longitude on the map. Ortelius shows the greatest dimension of the continent of South America as roughly equal to the distance from the westernmost cape of South America to the (enormous) Solomon Islands, whereas in reality the distance is nearly twice that.

Zoom out of the Pacific on Google Earth, and you see it become a full blue circle of almost all water; just a smidge of Mexico, a patch of Australia, and a sparse scattering of islands, like lonely jewels across an endless tableaux. Nothing like Ortelius’ map, which admittedly would be either mostly blank ocean, or very wide if it was a true projection.

Magellan took three months to cover the 18,000 plus kilometres from his entrance into the Pacific, then diagonally across it to the Philippines; an average speed of over four knots, which is a pretty good pace for well-worn, heavily barnacled carracks.

This brings us to the main ship gracing the chart. It is the Victoria herself, the image taking up a large part of the empty ocean. An angel guides the ship’s path, cannons fire a salute, sails are full and flags flying, crewmen work the ropes and a navigator holds an astrolabe on the quarterdeck. She is sailing westward, to immortality.

Other notable features of the map are that North and South America are named for the first time, California, until then regarded as an island, correctly becomes a peninsula, while New Guinea, previously thought to be an extension of Terra Australis, becomes its own island, though obviously with its south coast as yet unexplored. Its insular nature would not be proven until Torres sailed through his eponymous Strait in 1606. Considering the Caribbean was widely known and settled, its representation is rudimentary (as it is not the focus), while the western bulge of North America though detailed, is wildly inaccurate as it had yet to be properly explored.

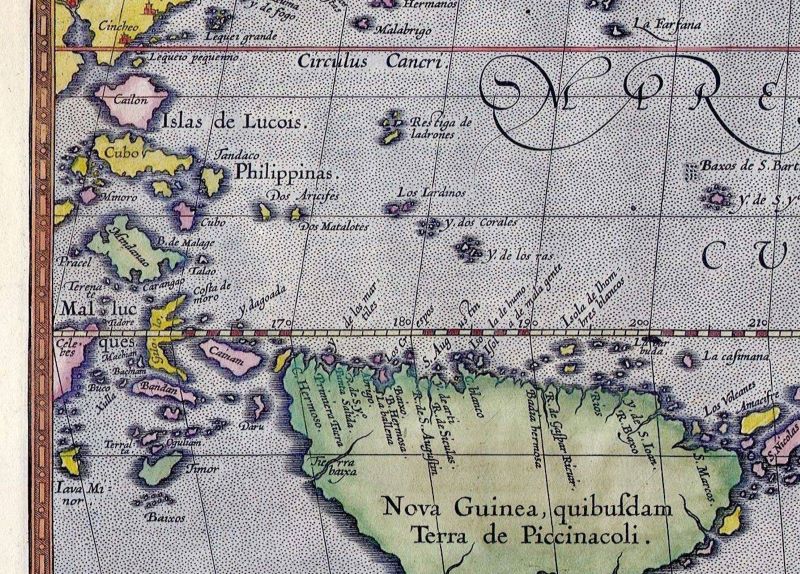

China is shown with little detail–though Canton (labelled Cantao), its major trade port is noted–and a Korean peninsula is vaguely recognisable, but Japan is dramatically misshapen (considering it had been known for two generations by the Portuguese), and the Isla de Plata above Japan is a fabrication, though Japan was famous for its silver (plata in Spanish).

And of course, in the south, we have the mythical Terra Australis, a fantasy perpetuated endlessly by mapmakers until the work of the Dutch in the seventeenth century showed the division between Australia and Antarctica. Part of this myth was an extension of the Ptolemaic concept of a landlocked Indian Ocean–the Pacific, and the Americas were not known to classical scholars–and part misunderstood reports going as far back as Marco Polo of a necessary antipodean counterbalance to the landmasses north of the equator.

Of greatest interest to most who gazed on this map in the last years of sixteenth century Europe was the central far western quadrant, for here lay the Spice Islands, labelled by Ortelius Mallucques (Moluccas). Known far and wide as the only source of clove and nutmeg trees, it was from these remote and mystical isles that the rarest and most expensive spices in the world came. Everyone was searching for them.

They were what Columbus had been seeking. And Diaz, Albuquerque, Magellan and Drake. Lying in the farthest reaches of Maris Pacifici between New Guinea and China, Java and the Philippines, north of Timor and south of Mindanao, we can see yellow coloured Gilolo, almost true to its real and very unique shape, and dissected by the equator. And just west of that, the legendary names can be discerned; Terenate (Ternate), Tidore, Machian (Makian), Bachian (Bacan) of the Moluccas and a single slab named ‘Bandan’ actually Ceram, but supposed to represent the Banda nutmeg isles, just to the south. Tiny pinpricks of land, bearing a weight of history out of all proportion to their diminutive extent.

Given the inclusion of the generalised locations of these tiny Spice Islands, but the omission of thousands of others, and the ‘rustic’ nature of representations of the Philippines, Java, Japan, Korea, New Guinea and the Solomons, it is fair to say that showing his audience where the legendary isles of spices lay was a fundamental reason for this map.

Another way of looking at Maris Pacifici is as a geographers route chart to the Spice Islands, but from the Spanish perspective; the Portuguese of course, came upon them from the Indian Ocean. Or perhaps rather, a demonstration of the immense endurance required to get there. The voyage from Europe to the tip of South America was somewhat understood at the time–it is around 12,000 kms–but onwards from there to the Spice Islands was another 18,000 kms. The immensity of the Pacific Ocean would have been hard to comprehend for medieval Europeans.

And in fact, for mariners as well. After the survivors of Magellan’s expedition returned to Spain in 1522, another Spanish fleet was dispatched to follow in its tracks around South America to the Spice Islands. It would be the last. Only one ship of the seven that left made the Spiceries; the emaciated survivors immediately disarmed by the Portuguese. Following that disaster, future Spanish expeditions were dispatched from Mexico or Peru, with only the vast Pacific to cross.

Drake and Cavendish both used Magellan’s Strait to enter the Pacific, as did the first Dutchman, de Weert in 1599, but LeMaire and Schouten a few years later discovered the easier–though wilder–route around Cape Hoorn, which would generally be subsequently used in preference to the narrow, torturous Magellan Strait.

All in all, Maris Pacifici is an engaging combination of mapwork and painting; of cartography and art, and an extension of the ongoing Renaissance theme of illustrating Europe’s growing knowledge of the world as realistically as possible. Today, it is one of the rarer maps of its class, as it appeared generally in atlases, from which many modern examples have been cut. Prime examples command prices of up to USD 17,500.

Sources for this post include Thomas Suárez’ Early Mapping of the Pacific, André Rossfelders In Pursuit of Longitude, and Lawrence Bergreens Over the Edge of the World.