The island we now know as Sumatra was known to the ancient Greeks as Sabadibae or Iabadium, to the early Chinese as Ye-po-ti, to the Indians variously as Javaka, Yavadesh or Suvarnadvipa, to the Arabs as Zabag, or Al-Ramni, and to medieval Europeans as Java Minor. So how did it end up becoming Sumatra?

The great wild island–sixth largest in the world–extends eighteen hundred kilometres from the Andaman Sea to the Strait of Sunda, blocking the passage between the Indian and Pacific Oceans like a brooding colossus.

Crossed by the equator, Sumatra’s dominant features are the Barisan Mountains, which track the western coast and include a web of 35 active volcanos soaring up to nearly 4000 metres, and geological instability. Wedged between the Indo-Australian and Eurasian Plates, the island is rarely tectonically quiet, with a repertoire of catastrophic events ranging from the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami way back to the cataclysmic Toba supervolcano–the largest eruption on earth in the last 75,000 years.

Human habitation of the island reaches back to Palaeolithic times, but the main events driving historic settlement patterns was the varying sea levels which stabilised at current heights only around 5000 years ago, and the arrival of the Austronesians from southern China around 2500 years ago. The Austronesians were a remarkable seafaring people who went on to sail outrigger canoes across seemingly impossible expanses of the Pacific and Indian Oceans to settle from Easter Island to Madagascar over the course of thousands of years. They were definitely sea-people.

While blessed with much-sought natural resources including camphor & benzoin, gold, tin, hardwoods and pepper, the difficult Sumatran landscapes–towering volcanos, raging monsoon-fed rivers, malarial swamps and dense jungle–made the sea a much more convenient thoroughfare than the land. Not to mention the cannibals and wild beasts that inhabited the rainforests which draped the mountains slopes.

But there were also many hazards in the surrounding waterways, including coral reefs, strong currents, shifting sandbars and tidal mudflats, and it took care and experience to navigate these. The northeastern tip of the island did however offer some positives for sailors. There was access to deep water, while there were also less reefs than in the south and west. Many river mouths provided shelter, refuge and good fishing. The area stood at the confluence of several seasonal wind systems, including the winter monsoon, the southwest monsoon and the southeast trade winds blowing up from the west Australian coast. And couched between the Barisons and the Malay mountains across the Malacca Strait provided sheltered conditions for trading ships and merchants.

The first significant regional contact for Sumatra began with maritime links to India, going back further than 2000 years. They referred to the island as Suvarnadvipa, the ‘island of gold.’ A few hundred years later, Roman sea trade with India commenced. The second century scholar Ptolemy mentions Barus–a legendary camphor port of Sumatra–in his encyclopaedic Geography indicating that the big island was just on the Roman radar. They just were not clear it was an island.

Around this time, spurred on by increasing maritime trade, Southeast Asian societies began to develop regionally into empires. First there was Funan in Indochina, but as it declined, Srivijaya, based at Palembang in southern Sumatra took the lead. Their empire lasted from around the fifth to the twelfth century, and dominated much of Sumatra and the Malacca Strait and controlled all the burgeoning trade between India and China.

But empires grow stale and old, and Srivijaya also declined after a conflict with the Cholas from India, and was replaced by a series of Javanese-based empires. Kedah in Malaya and a scattering of very strategically placed little pepper ports in north Sumatra had been loose vassals of Srivijaya, and they took the opportunity of weakening control to assert a more independent trading policy.

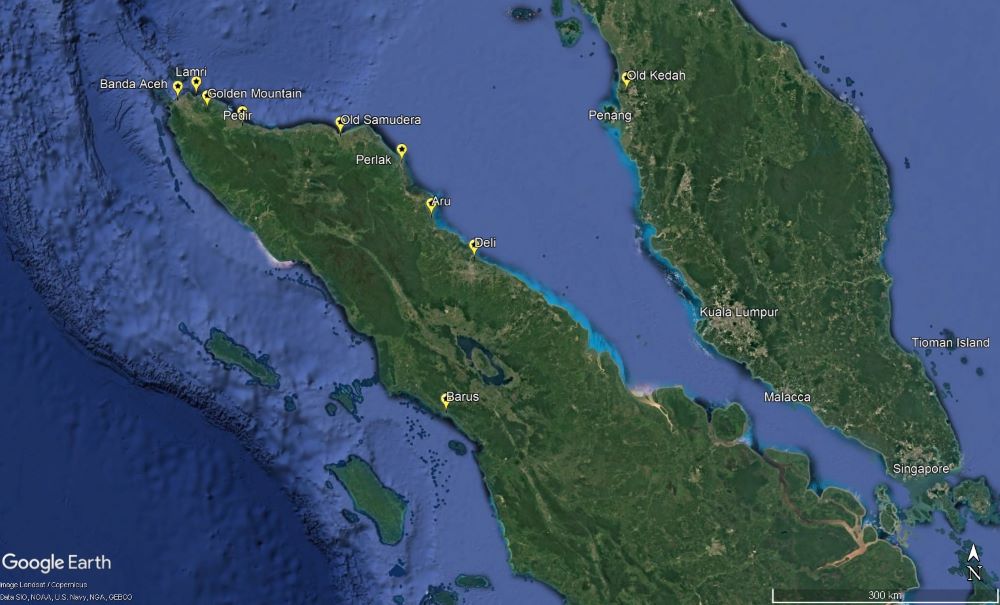

From the twelfth century, near the northern tip of Sumatra, small ports emerged serving the Chinese, Indian and Arab traders who arrived from different directions on the winds of the monsoons. Lamri seems initially to have been pre-eminent of these, being recorded in Arab, Chinese, Armenian, Javanese, Malay, Tamil and Venetian sources from as early as the ninth century. A derivative of its name was used by Arabs to refer to the entire island, al-Ramani. They sent embassies to China twice in the late thirteenth century.

But competition ultimately was king and harbours thrived at nearby Aru, Deli, Tamiang, Perlak, Pasai, Lamri, Aceh and at another river-mouth called Samudera. All vied to attract the traders which generated income. Samudera in Indonesia means ‘sea’ or ‘ocean,’ or in the context of a port, ‘ocean edge’ and its maritime links seem the likely reason for this name.

By the thirteenth century, most of the traders arriving from the west were Arab or Indian Muslims, and, so the story goes, an Indian adventurer landed in the area, converted to Islam, founded the twin cities of Samudera- Pasai, and began to attract more and more traders. The two ports lay near the mouths of adjacent river mouths, and standing at the tip of Sumatra were well placed for merchants to sell their wares without sailing deeper into the pirate-ridden Malacca Strait. Also nearby was an 1800 metre sugarloaf-shaped volcano called the Golden Mountain that shone like a beacon to navigators arriving after crossing the Bay of Bengal from India.

The adventurer was called Sultan Malik al-Salih, and he is now revered as Indonesia’s very first Islamic ruler. His tomb lies amid the museum complex at Samudera, where the tombstones of 18 of the sultanate’s 24 sultans have also been located.

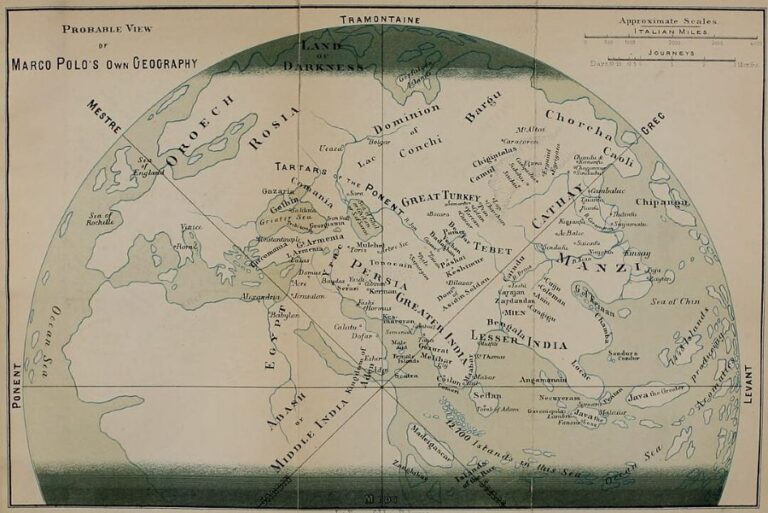

Samudera dispatched ambassadors to China in 1282 named Suleiman and Hussein (obviously Muslim), and the sultan’s tomb dates from 1297. A few years earlier, Marco Polo sailed up the Malacca Strait from China, escorting a princess to Hormuz. While waiting for the winds of the winter monsoon to take him across the Indian Ocean, Polo recounts staying for five months at Samudera, which he calls Samara. He described a primitive trading port where the Chinese accompanying him built a stockade to defend against raids by cannibals.

Another Italian, Friar Oderic sailed from India to China around 1322 and described passing Sumoltra as the name for Polo’s Samara. Like Polo though, he was describing a city, not the entire island. However, also in the early thirteenth century, a Persian geographer, Rashid al-Din mentioned the island of Sumutra. Getting closer. In 1355, Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta in an account of his extensive travels refers to the island as Samutra. Fourteenth century Arab navigational texts describe the island as Shumutra. Nearly there.

Finally, another Italian explorer, Niccolc di Conti in a 1447 report of his travels through Asia provides the name Sumatra. This is the first known mention that matches the modern English toponym for the whole island.

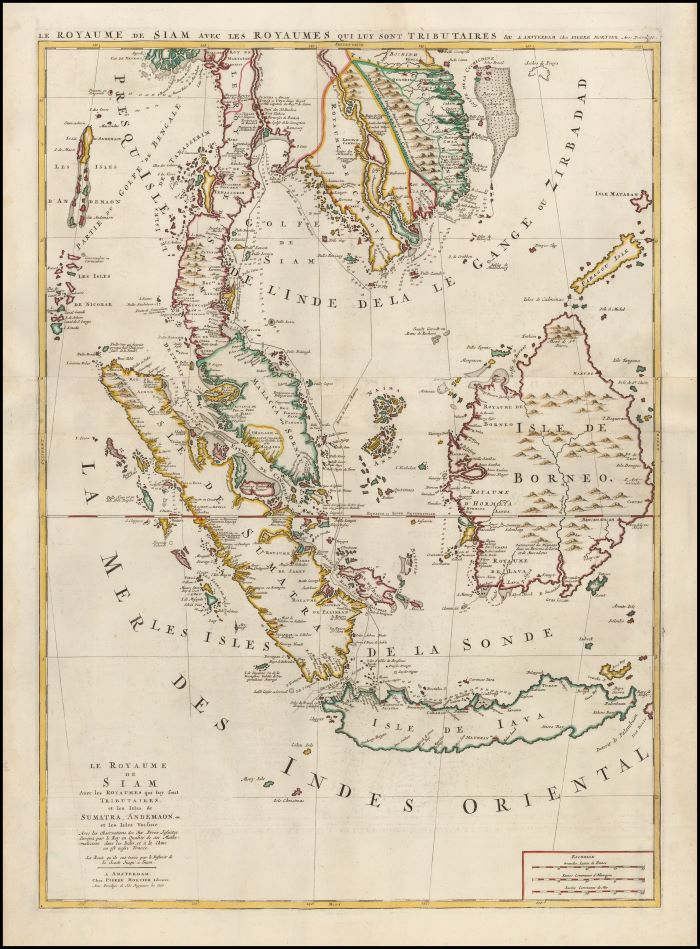

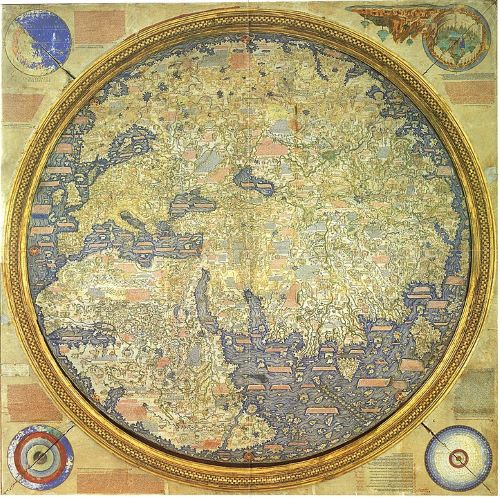

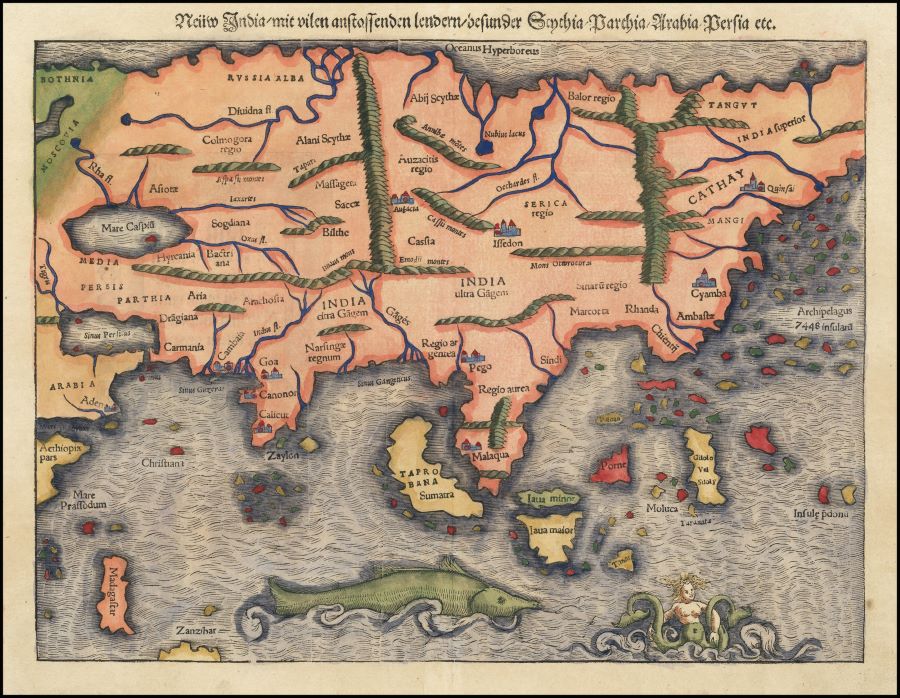

In relation to the name appearing on maps, things get confusing. This is because ever since the time of Marco Polo, mapmakers got the great islands of the Indies confused. What we now know as Sri Lanka, Sumatra and Java were often interchangeably mis-labelled. Tabrobana referred to Ceylon or Sri Lanka, but was also applied to Sumatra. Java and Sumatra were generally known as Java Major and Java Minor respectively, but often mixed up. So, the name Sumatra first appeared on a map in 1538. But it referred to Ceylon, not Sumatra.

Ultimately in 1540, Sebastian Munster applied Sumatra to Sumatra. While he added Tabrobana to the island as well, just to hedge his bets, it was the first known map to name the island as we know it today.

Samudera, the sixteenth century pepper port, was not long at the top in north Sumatra. Lamri fell to an expanding Aceh mid-century, Pedir followed, and Samudera itself was overrun soon after. The site is now a scattering of coastal villages lapped by the tropical seas and cut by silty rivers draining the monsoons off the mighty Barisan Range.

But if you’re ever there, and you ignore the racing mopeds and blazing sunshine, and you let your mind drift away under the palms while watching the green-brown river flow by, you can almost imagine Polo or Battuta aboard a junk drifting up to a wharf loaded with pepper bales, and men from Hormuz and Calicut and Canton unload silks and porcelain for exchange, and bantering away as traders do.

Sources for this piece include Thomas Suārez’ essential Early Mapping of Southeast Asia, Henry Yule’s Cathay and the way Thither, Paul Michel Munoz’ Early Kingdoms and William Marsden’s History of Sumatra.