The Spanish carrack Victoria was the first ship to circumnavigate the globe, leaving Seville in September 1519 and arriving back three years later after an incredibly arduous voyage. Four other ships and 250 crewmen were lost along the way. Just 18 men completed the epic journey, becoming (probably) the first circumnavigators.

The expedition was dispatched on the orders of King Charles, the new Spanish monarch. Charles was jealous of the success his neighbour and rival Portugal was having selling the spices of the Orient to the markets of Europe. Portugal had reached India in 1498 by sailing around Africa and a decade later had found the Spice Islands, while Spain remained thwarted in the race to ‘the Indies’ by the barrier of the Americas.

Previously, Papal adjudication had (rather arrogantly) divided the undiscovered regions of the world between the two Iberian kingdoms under the Treaty of Tordesillas, with the goal that apart from plunder, exploitation and trade, they should convert newly found heathens to Christianity. The division was set at a meridian of longitude in the Atlantic around 2000 kilometres west of Portugal’s Cape Verde Islands. Portugal was lord of lands to the east: Brazil, Africa and India, and Spain would rule those to the west; the Americas except Brazil.

What was to occur at the anti-meridian, or on the other side of the world where the line of longitude through the Atlantic extended around the poles into the Pacific, was not foreseen or addressed. In those days you couldn’t be absolutely sure of your exact location on the other side of the world. So, no-one was really clear on whether the Spice Islands lay on Spain or Portugal’s side of the line.

Ferdinand Magellan

Enter, Ferdinand Magellan. A battle-hardened knight, a proven warrior, an experienced sailor and a practiced navigator, Magellan was Portuguese, not Spanish, a renegade from his homeland. He had served Portugal in India and Africa, and had been part of the force that captured Malacca–Asia’s spice emporium and reputed at the time to be one of the richest ports in the world. Disgruntled with his homeland, he convinced King Charles and his courtiers to fund an expedition to prove the riches of the Spiceries belonged to Spain and not its Iberian competitor.

Running an empire like Spain’s was an expensive task, and any plans to supplement the kingdom’s income–with spice profits for example– were regarded very favourably. Even though Charles purloined a recent gold shipment from the Caribbean, he still needed to borrow from the wealthy German Fugger family to finance the enterprise, which equated to roughly three million of today’s dollars.

Magellan knew Asia, understood navigation and cartography, and spun a convincing tale–with the help of charts, calculations, a globe and learned mapmakers–and Charles appointed him commander of the Moluccan Fleet. Magellan’s route would not follow the Portuguese around southern Africa and across the Indian Ocean, but would find a passage south of the Americas that he had convinced the Spanish existed, and then cross the Pacific, the extent of which was then absolutely unknown.

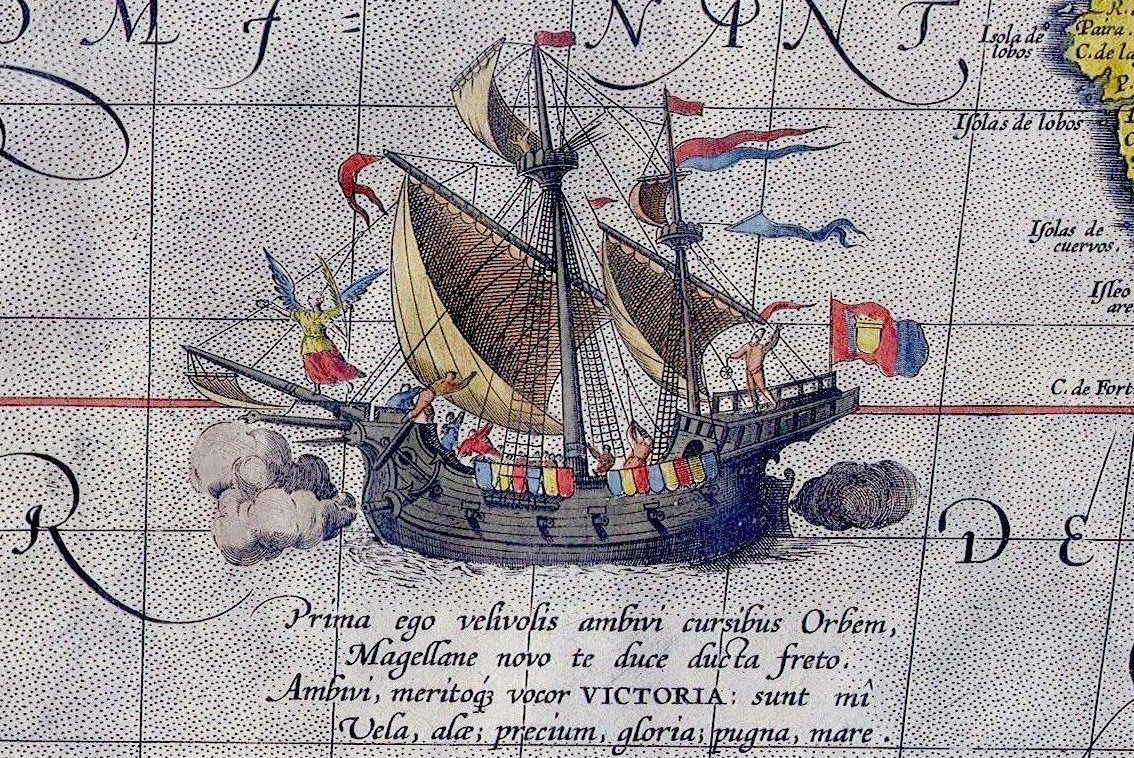

The fleet consisted of five ships, four, known to the Spanish as carracks, the largest of which displaced just 120 tons, and one diminutive caravel. The Victoria, at 85 tons, the second smallest, was square rigged with three masts. She carried main and top sails on her front masts, a lateen on her mizzen, a spritsail on her bowsprit and ploughed across the Pacific at an average of two or three knots. She started with a crew of about 55 and was just 20 metres long.

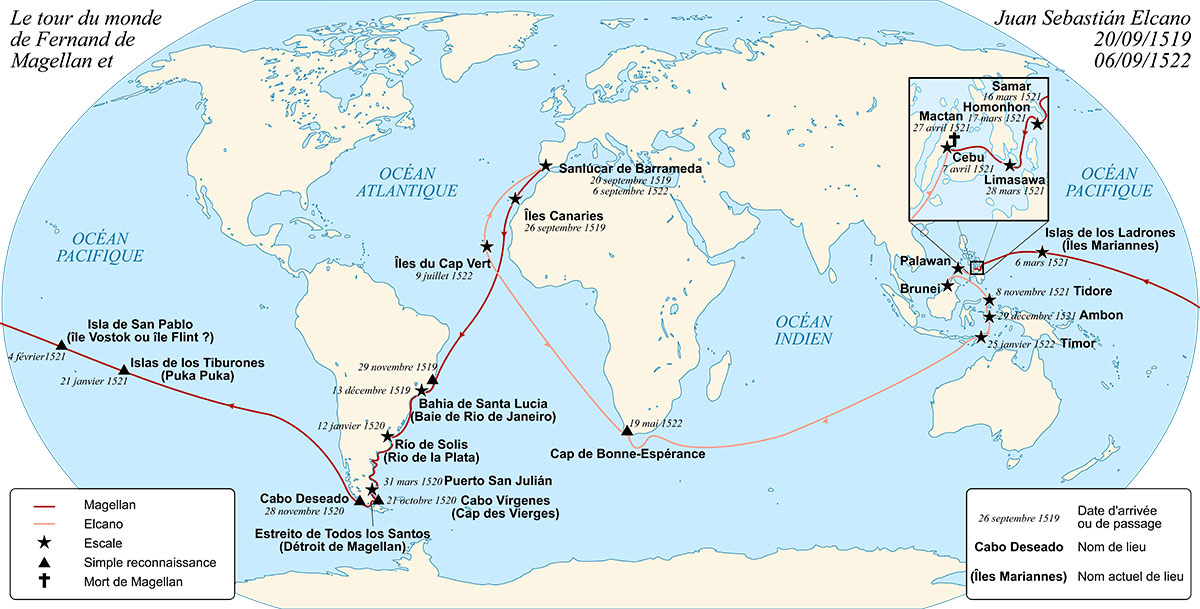

The little fleet sailed down Seville’s Guadalquivir River and left Europe at the end of summer, making the bay of modern Rio in three months. As they sailed south from there, conditions grew bleaker and there was discontent among the mainly Spanish crews to be under Portuguese command. Magellan had to put down a mutiny, and one ship deserted and sailed back to Spain. Another was wrecked. During a torturous, storm-whipped southern winter, three ships finally entered the Pacific at the end of November 1520 after navigating the twisting Magellan Strait–finding it very close to where Magellan had said it was to be found. But their travails were only beginning.

It took four long months to then cross the Pacific, the extent of which Magellan had substantially underestimated, and they thankfully dropped anchor in the Mariana Islands in March 1521, eighteen months after leaving home. Two weeks later they ‘discovered’ the Philippines, which Spain would go on to rule for nearly four hundred years.

It was here on the island of Mactan that Magellan was killed in a skirmish with a local chieftain, Lapu Lapu. In an ambush a few weeks later, another two dozen-odd crew were killed, including the replacement commanders. Now unable to man all three ships, they burnt one, leaving just the Trinidad and the Victoria. Understandably lost, they wandered the seas, stopping at Brunei and Mindanao, until finally, with a captured guide, they sighted the soaring volcanos of the Spice Islands in November 2021.

Anchoring at Tidore, one of the major centres of the clove-bearing Moluccas, they were welcomed by its sultan, whose ardent rival, Ternate lay clearly visible just across the water. The Portuguese had a trading base on Ternate, and an alliance with its sultan. Knowing of Magellan’s squadron and its route, Portugal’s King Manuel had, some time before, dispatched his own fleet to intercept the renegade, and to build the first of the Spice Islands Forts at Ternate.

Juan Sebastian Elcano

A treaty signed with the sultan, and a hold of priceless cloves loaded, the Spanish were keen to return home. But the Trinidad needed repairs, and so it was the little Victoria alone that unfurled its sails and steered southeast in late 1521, under the command of Juan Sebastian Elcano, heading for Spain.

She cleared Timor and in three months arrived at the Cape of Good Hope amid the howling gales of the southern autumn. Two challenging months later, she pulled into the Portuguese Cape Verde Islands for provisions. The crew by this stage were exhausted, starving and terrified of both Portuguese arrest and the possibility of treason charges in Spain. A group of sailors sent ashore for food was detained, and with heavy hearts, the others had to leave their comrades behind.

They sailed northeast, pumping the leaking holds constantly, all on the edge of death. Early in September 1522 they stood off Cape St Vincent near Sagres–the site of Prince Henry the Navigator’s original oceanic exploration training school, built to encourage the ultimate journey they had just made–and on 10 September 1522 they were towed up the river to a fitting hero’s welcome in Seville.

Elcano, a Basque from northern Spain was for a time feted by king and country, and set off for another voyage across the Pacific before succumbing to disease in 1526. Despite participating in the mutiny against Magellan–and subsequently crossing the Pacific in chains until released after Magellan’s demise–Elcano is more fondly remembered by Spaniards for completing the circumnavigation, while Magellan is celebrated by the Portuguese for planning the whole enterprise. Spain recognised Elcano’s achievement by naming their beautiful 95-year-old four masted barquentine naval training ship after him.

Made of stout Cantabrian oak in Biscayan shipyards, the original plucky Victoria made two subsequent Atlantic crossings to Hispaniola but was lost with all hands on the final return passage. Nevertheless, she achieved immortality by becoming the very first ship to complete a circumnavigation, totalling over 35,000 nautical miles. A great replica has been built for the 500th anniversary and can be inspected and sailed out of Seville. See more at www.fundacionnaovictoria.org/nao-victoria.

But who was the first man to circumnavigate the world? Certainly, Elcano and the 17 men that pulled into Seville with him in summer 1522 are front runners. But did anyone beat them? One theory is that Magellan himself deserves the title. While there was a gap between Malacca (102 degrees East) where he had sailed under the Portuguese flag in 1511 and Mactan (124 degrees East) where he died in 1521, some speculate that in the eighteen months he spent in Malacca he undertook unrecorded journeys in the region that may have taken him east of the Mactan meridian. While it would be fitting for the brilliant, determined man with incredible vision and willpower that set the first circumnavigation in motion, there is no evidence that he did so.

Similarly, Magellan’s slave Enrique, acquired in Malacca but variously described as of Malayan, Sumatran or Filipino origin, also accompanied the first circumnavigators across the Pacific, but the last we hear of him is on Mactan, so it is impossible to say if he deserves the title. Similarly, there were a number of other Portuguese–some masquerading as Spaniards–who may have served in the Indies fleets prior to the Spanish expedition, which would have allowed them to claim first place as they sailed back past India in 1522, but again, there is no convincing evidence.

One other intriguing possibility is Francisco Albo, a master’s mate from Rhodes, who returned on the Victoria. He would have crossed his home meridian as they approached the Cape of Good Hope, before the others crossed their outward track near Cape Verde, so technically at least, perhaps he deserves the medal.

In any case, the job was done, the first and most gruelling circuit of the earth was complete, and by a small ship we tragically have no surviving image of. Begun by a Portuguese renegade, financed by a Holy Roman Emperor and a German banker, completed by a Basque mutineer, and crewed by Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, Norwegian, Flemish, French, German, Italian, Irish and English sailors (a European project!), a small fleet losing ninety percent of the crew and eighty percent of its ships had drawn its mark around the globe. It was the first to cross the Pacific, sail all the other oceans on the planet and it showed science the true girth of the earth. With a load of cloves from the Spice Islands, King Charles had turned a profit, and immediately set about planning his next armada…

For further reading on this subject, I recommend Tim Joyner’s Magellan, Laurence Bergreen’s Over the Edge of the World, and Andre Rossfelder’s In Pursuit of Longitude.