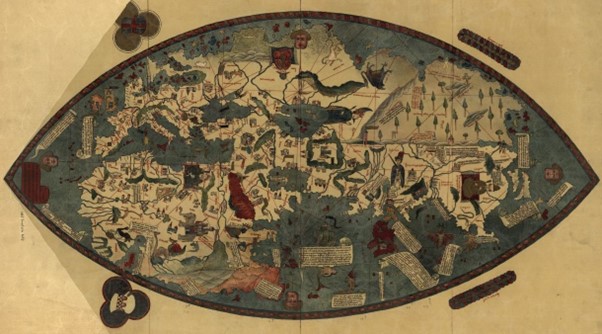

The Genoese Map of 1457, produced by an unknown mapmaker included data from Conti shows Banda (labelled Bandam) the dark red island at extreme lower right. This was the first time one of the Spice Islands had been shown on a map. The map is held at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence, courtesy Wikipedia.

What are the Spice Islands?

The legendary ‘Spice Islands’ refers to two separate island groups in the east of modern Indonesia; the Moluccas (now province Maluku Utara) astride the Equator, and the Banda Islands (now province Maluku), six hundred kilometres to the south. Timor is further southwest, New Guinea to the east, Sulawesi to the west and the wide expanse of the blue Pacific towards the sunrise.

Until some opportunistic replanting in the eighteenth century, the Moluccas were the only place on the face of the earth that reared clove trees, and the Banda’s the single source of nutmeg and mace, two priceless parts of the same rare nut. Ambon, lying between the two island groups, and the best harbour in the area links the two island groups into the combined Spice Islands.

Though most famous of the spices, cloves and nutmeg join with camphor and pepper from Sumatra, sandalwood from Timor, cinnamon from Ceylon and ginger, cardamon and turmeric from India to form the bulk of the historic spice trade. Long distance trade in these spice goes back past Roman times, into the darkness of unwritten history. Scholars like Strabo, Herodotus and Ptolemy all noted the spice trade, and cloves were recorded in China three centuries before Christ.

Before the fifteenth century, there is no convincing evidence of the location of the Spice Islands on maps anywhere, European, Persian or Chinese. Apart from those across the great archipelagos, no-one had the faintest idea where the spices came from. They were carried by Austronesian sailors in local shipping to the ports of Java, Sulawesi, Borneo and what are now the Philippines. From the sixth century the main route was through the Srivijayan Empire, based at Palembang in Sumatra. Once there, they were shipped north across the South China Sea, or west to India. And on to the Red Sea or the Persian Gulf. From there by camel to the Levant or Alexandria. And from there in the ships of Venice and Genoa across the Mediterranean and then over the Alps to northern Europe.

As the Spice Islands were very remote, not easy to find (and keeping it that way assisted higher prices being charged), and because of the seasonality of the monsoon winds, even adventurous Asian traders preferred to wait for local sailors to bring the spices to them in Java, Macassar or Malacca. Persians, Arabs, Indians and Chinese then carried them onwards. This is how the system worked until the Portuguese–vanguard of the colonial powers–arrived in the sixteenth century.

One of the first glimpses we get of the Spice Islands is from Marco Polo, who travelled overland to China, then back by sea to Hormuz via the Malacca Strait. He noted that all kinds of expensive spices were available on Sumatra, where he waited for five months between monsoons in the thirteenth century. Two hundred years later, another Venetian, Niccolo Conti mentioned the islands of Bandam and Sanday as the source of nutmeg and cloves, though he was hazy on where they lay.

With input from Conti, this enthralling map included the first of the Spice Islands to be (roughly) charted in 1457 (see above). It also showed an open Indian Ocean, which previously had been assumed to be enclosed and therefore inaccessible from European seas.

By the time this map appeared, the Portuguese were already working their way down the west African coast, seeking a passage around Africa into the Indian Ocean, and then spices and Christians. Finding the Spice Islands was one of their primary goals. They captured Ceuta in modern Morocco in 1415, founded a castle at Elmina on the Gold Coast (now Ghana) in 1481, rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, and sailed to India ten years later. Here they found the nutmeg and cloves they were looking for, but also learned they had arrived from much further to the east.

They set up a trading post at the emporium of Malacca in 1509, but it was a Muslim Sultanate, and Christians were not welcome. The traders were soon imprisoned, and it was up to Afonso Albuquerque to free them and capture the port two years later. The Sultanate was protected by twenty thousand pirates (the Sea People, or Orang Laut) and armed with 3000 cannon, and so it was a fierce battle that took the Portuguese months to win. Albuquerque wasted no time, and while building a fortress and re-constructing the battered city, he dispatched a small expedition far to the east to find the Spice Islands.

From the time they entered the Indian Ocean, the Portuguese had initially relied on local pilots for navigation and had even captured some intriguing local sea charts of Asia–tragically none of which survived–to find their way around. Once new routes were surveyed, the details were recorded in sailing instructions (rutters) and their own portolan charts produced for future use, but these maps were closely guarded. As a consequence, the rest of Europe remained for a long time ignorant of the amazing exploits of the Portuguese, and the geography of Asia.

Who discovered the Spice Islands?

Combining local maps, interviews with local sailors and with three Malay pilots aboard, two carracks and a caravel set out from Malacca in December 1511, seeking to finally put the Spice Islands on the map. With the east monsoon pushing them down the island chain, they passed Java, Madura (where one of the carracks was wrecked), Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa and Flores before turning northeast for Banda. Contrary winds kept them on nearby Ceram for three months, waiting for the northerlies. When these arrived, it was just a couple of days sail.

First, the dramatic volcanic peak of Gunung Api would have emerged out of the Banda Sea, visible from a ships deck over 90 kilometres away. It was early in the monsoon, which can be an unsettled time, so they may have sailed through towering tropical thunderstorms and taken a drenching of warm rain as they closed in. The sails filled with a light breeze from their starboard side, and melonhead whales might have frolicked in their wakes. Gradually, the lush jungle-covered hills took shape. The long hilly arc of Lonthor Island curved behind the volcano’s spire, and a lower, smaller island stood before it. That held Banda township and harbour; ‘capital’ of the islands. Far in the distance and slightly to the right was a distant island, now called Ai, and closer but off to the left was tiny Rosengain. Apart from these handful of specks, the great Pacific was empty to the horizon in every direction.

And so presently, this group of a few dozen ragged Portuguese sailors dropped anchor in the crystal-clear waters at Banda, under its towering volcano. The first recorded journey to the Spice Islands, and the first Europeans to sight these mystical, magical islands.

Over the channel across the rolling hills of Lonthor they could see groves of small light coloured fruit trees; these were the bearers of nutmeg they had crossed the oceans of the world to find. Soon they would find out that cloth purchased in Malacca for one copper coin (a real) got them half a kilogram of the mace coating of the nutmeg from the islanders–worth seven times the ground nutmeg itself. And back in Europe, that weight of mace was worth 350 of the same coins, a profit of 35,000% !!

Two thousand sea miles from Malacca, and fifteen thousand from Lisbon, they had finally found the Spice Islands and put them on the map. Or half of them, anyway. What they had located was the nutmeg Banda Islands, but the clove-growing Moluccan Island were a week’s sail to the north, and that was now where the wind was blowing from. That same north wind could however carry them back to Malacca with their holds full of nutmeg. The clove islands would have to wait. They had fortune enough aboard. After a month in the Bandas, the Portuguese hoisted their anchors and sailed off towards the setting sun, back to Malacca, arriving a year after their departure.

Francisco Serrão

Francisco Serrão had captained the carrack that was wrecked off Madura, earlier in the journey. He and his crew had been taken aboard the other two ships, and sailed with them to Banda. There, the commander had bought him a local junk to load with nutmeg. But as the three ships sailed away, a storm wrecked the junk on a reef in the Lucipara Islands. Serrão was shipwrecked for a second time!

It got worse for Serrão and his handful of comrades; pirates spotted the wreck and approached to plunder. But the Portuguese had salvaged their arms and armour and turned the tables on their attackers, commandeering their ship. They wandered through the island for a time as guns for hire. Across a seascape of warring chieftains, they were in great demand. Soon, word carried to the local superpowers, clove islands Ternate and Tidore in the Moluccas. A squadron of Korakora were dispatched to pick them up by the Sultan of Ternate who wanted them to join his forces.

And so, a few months after ‘discovering’ the fabled Banda nutmeg Islands, Serrão became the first European to set eyes on the Clove Islands, also set amid spectacular tropical volcanic landscapes that must have seemed indeed from another world.

More on Serrão, his good friend Ferdinand Magellan and their plans to rule the Spice Islands coming soon!