Once you start looking, there seems to be no end to the tragedy of wonderful maps lost to history. So much knowledge and effort and science, laboriously compiled over years or decades, excitedly incorporating new discoveries on parchment as explorers dock their ships, all discarded, wasted. Often lost forever.

In some cases, we are left with traces, or glimpses of what was and is now no more. This was the case for the Javanese map that came into Portuguese hands in 1511, but was subsequently lost in a shipwreck.

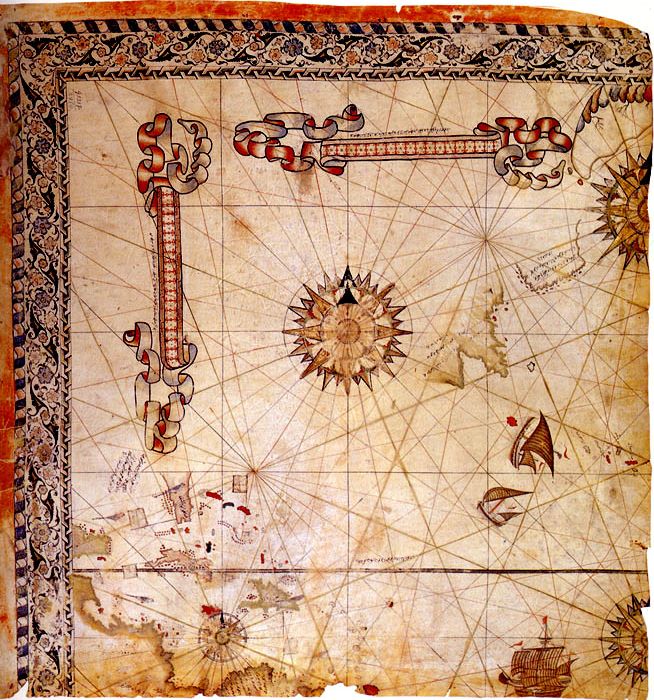

It is also the case in a near contemporary ‘cousin’ of the Javanese Map; the Ottoman Piri Reis Map of 1513. Of this map, we still have a tantalising sliver. A surviving western third that shows the least fascinating segment (the Atlantic), which merely awakens our interest in the lost sections even more.

Piri Reis (reis meaning admiral in Turkish) was an Ottoman mariner born at Gallipoli around 1470 and lived under four sultans: Mehmed II, conqueror of Constantinople; Bayezid II, who ruled for thirty years; Selim I who defeated the Mamelukes in Egypt; and Suleiman The Magnificent, who captured Belgrade and Rhodes, and eventually had his favourite admiral beheaded.

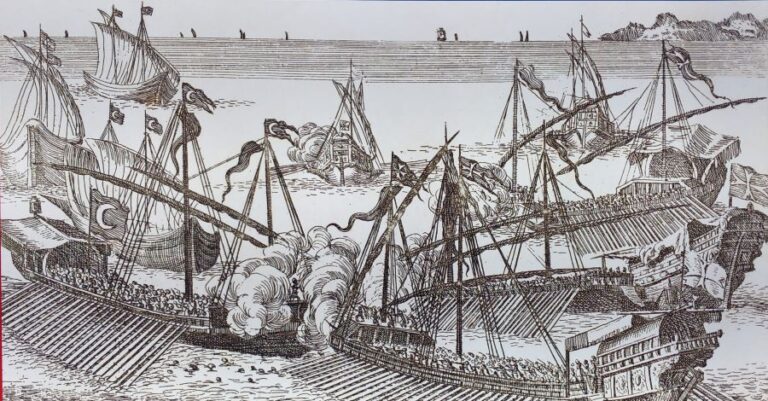

The power and conquests of the Ottomans reached their peak during Piri Reis’ life, and along with formidable military might its naval power evolved. His uncle, Kemal Reis was a legendary corsair, famous for his exploits against Christian–especially Venetian and Spanish–shipping in the Mediterranean, and Piri learned the brutal trade from an early age.

Operating initially from the Barbary Coast of North Africa, they captured ships, stormed fortresses and witnessed the carnage of large-scale galley warfare first hand. Piri and his corsair colleagues were soon incorporated into the nascent Ottoman Navy, such experienced corsairs forming the backbone of the previously un-nautical Turks. Piri first commanded a galley, then a squadron blockading Rhodes and Alexandria and finally in 1546 he was promoted admiral of the Ottoman Fleet in the Indian Ocean. At this time, Portuguese fortresses and fleets controlled much of the Persian Gulf, and they were actively threatening the Red Sea, with even an extremely ambitious proposal to capture Mecca. Portuguese ships and firepower however were superior to his galleys and, following a retreat from Hormuz, Piri Reis was found guilty of dereliction and executed, after a lifetime of service, at the age of 80!

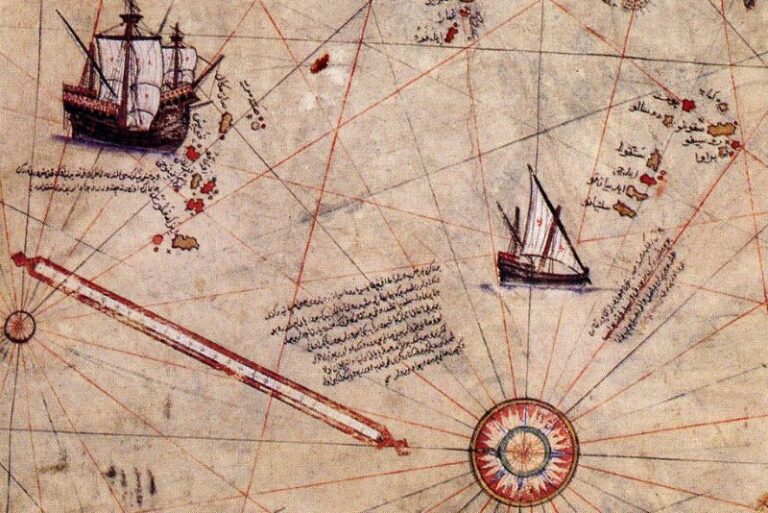

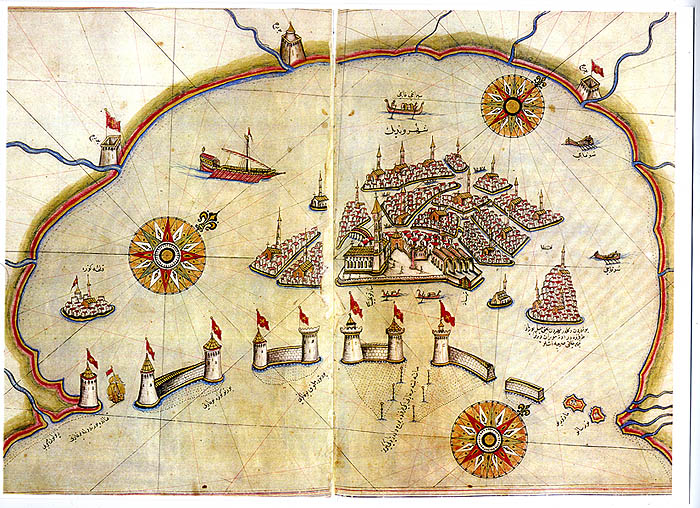

During his extensive maritime career, he had taken a great interest in charting and maps of his areas of operation, and he left three great works as his legacy. His Kitab-ı Bahriye, or Book of Navigation is a nautical almanac of the Mediterranean, and less so the Indian Ocean, providing stunning portolan charts, route instructions, observations of tides and currents, predominant winds and all the tools for mariners. And every page gleamed from decades on the deck of ships and galleys roaming the seas for prey. It is a sixteenth century treasure, and while no originals survive, many later copies do. The first version was completed in 1521 and gifted to Sultan Suleiman, while a second version was presented to the Grand Vizier in 1526.

Secondly, he left his last major work, a 1528 World Map; of which again, tragically, only a smidgin of one corner remains.

And lastly, of course his first World Map, of 1513. In its complete form, and in the spirit of the Javanese Map, this was a map of the known world. Of the continents, only Antarctica would have been missing. Piri lists his fascinating array of sources as ‘twenty maps as well as mappamundi,’ including:

- Eight World maps that go back to Alexander the Great

- An Arab map of India

- Four Portuguese maps representing India and China

- A post-Colombus map of the Americas

- At least six other source maps that are not defined

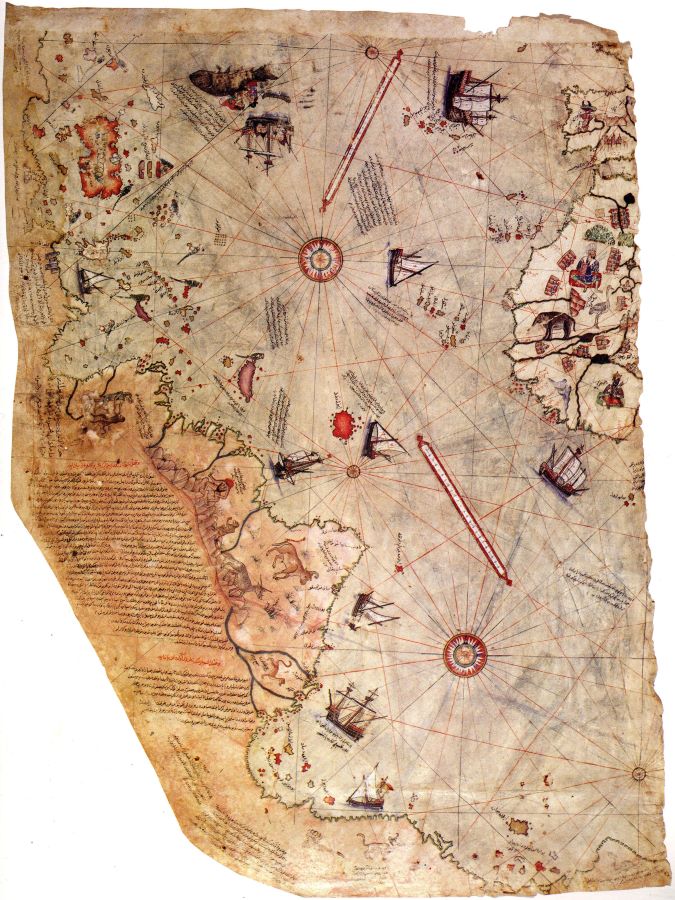

As such it was one of the widest ranging of contemporary maps, extending from South America to probably Sumatra and possibly Japan, and from France south to the Cape of Good Hope. It was centred on the eastern Mediterranean, but included the North and South Atlantic and no doubt the Indian Ocean as well as the Red Sea and Persian Gulf, with which Piri would later become very familiar. In style it is presented as a portolan chart; a practical navigators map with rhumb lines and windroses, made for making courses across open water and for coasting from landmark to coastal landmark.

But not only is it a mariners tool; it is also a work of artistic beauty, decorated with calligraphy, inscriptions, colourful figures and creatures, contemporary ships, and of course, islands, reefs and other hazards, all hand-drawn on parchment from gazelle skin. So fantastical are some of the illustrations–blemmyes, cynocephaly and centicores–that this gives hints about some of the map’s provenance, and makes us yearn more for what we would find in the missing parts. Piri himself said the map ‘showed twice as much as other maps’ which is impressive when we look at his obvious and likely sources.

SOURCES

As Piri mentions, among his base sources were what he called the eight maps of Alexander the Great. This refers to the works produced by Claudius Ptolemy; Roman-era maps dating from the first century Geographia, drawn from all the knowledge of the Greeks and Romans since the time of Alexander’s exploits that extended as far east as the Indus River in modern Pakistan, and north to Bactria near modern Afghanistan. These were lost to medieval Europe and luckily only preserved in the Muslim world until rediscovered during the Renaissance. Piri seems to fall back on Ptolemy when no other source is forthcoming; an example is South America joining Terra Australis in the Ptolemaic manner, but not southern Africa, as had been proved by the Portuguese.

The rapid Ottoman expansion from nomadic herders to a mighty empire that snuffed out thousand-year-old Rome (Constantinople) and threatened Europe only slowly dragged science along with it; Piri Reis is the most notable of its cartographers, but there were other sources in the Islamic world that likely provided some of his content. The Golden Age of the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1250 AD) produced some learned geographers such as al-Idrisi (1099-1165), and texts like Buzurg’s Wonder of India, and Khordadbeh’s Book of Roads and Kingdoms that are also likely sources.

Also mentioned is an Arab map of India, and this may represent a fairly broad use of the term India, perhaps even more correctly the Indian Ocean extending as far east as Sumatra. The sultans ruled Arabia at the time and though Arab geographers were not as widely known as, for example, the North African al-Idrisi, al-Khwarizmi of Bagdad or Persian al-Biruni, and no comparable Arab maps to Piri Reis’ have survived, they had certainly been navigating the seas from the Persian Gulf all the way to China since at least the ninth century, so it is very likely that some form of navigational charts existed and were possibly used for the 1513 Map.

Very clearly, Portuguese maps and portolan charts were a major influence on Piri Reis. Firstly, because at the time the Portuguese were the most widely travelled mariners on the planet, and secondly because they were very proficient cartographers able to portray both practical operational concepts and spectacular, decorative artwork on the same chart. The Indian Ocean chart from Diego Homem’s Universal Atlas is an example of both concepts demonstrated on the same parchment. From the standard and style of illustrations on his World Map, it is clear that Piri Reis utilised contemporary elements from Portuguese charts.

But it was not just Portuguese charts that he utilised from the infidels; he also notes that a ‘map of Colombus,’ or a Spanish map was used. In one note on the surviving map segment, Piri acknowledges that a captured Spaniard–certainly an officer and probably a chart-carrying navigator–provided the details of the Americas from recent maps, probably dated to Colombus’ third expedition. It seems the Americas depicted are from a blend of Portuguese and Spanish maps, as the former liked to portray no passage south of the Americas, as Piri’s Map shows, so as to discourage Spanish attempts to gain the Spice Islands from the west. Magellan’s expedition would disprove that not ten years after Piri’s Map was first completed. The Portuguese were not sufficiently familiar with the Caribbean and Central America, which are clearly reflected in Piri Reis’ map and so derived from Spanish sources.

Two sources not mentioned are Chinese or Southeast Asian, which we know from the Javanese Map were available at the time, just probably not to the Ottomans. The sultans would in time establish tentative relations with Aceh on Sumatra to assist in combatting the Portuguese, but this was much later in the sixteenth century. In any case, Piri obtained data on these areas from contemporary Portuguese charts–although as they only arrived in China in 1513, charts would not have been available yet. And of course, Piri’s navy would have to capture Portuguese maps on Portuguese ships; they would never have been given up without a fight.

So what happened to the map? Well, Piri presented it to the sultan in 1517, but his reaction is unrecorded. The map was filed away and lost in the Ottoman archives until 1929, when the remaining fragment was discovered. Perhaps the sultans were not big on astonishing world maps.

One bizarre outcome of the rediscovery of Piri Reis’ map has been a number of crank theories that conflate his depiction of South America and Terra Australis with clear evidence that these were mapped by aliens from space or perhaps evidence of an advanced civilisation inhabiting an ice-free Antarctica, and that somehow, Piri got hold of their maps, and included their data in his own. If you like delving into such theories – and keep in mind here Antarctica was last ice-free 10 million years ago – Charles Hapgood’s Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings is the place to go.

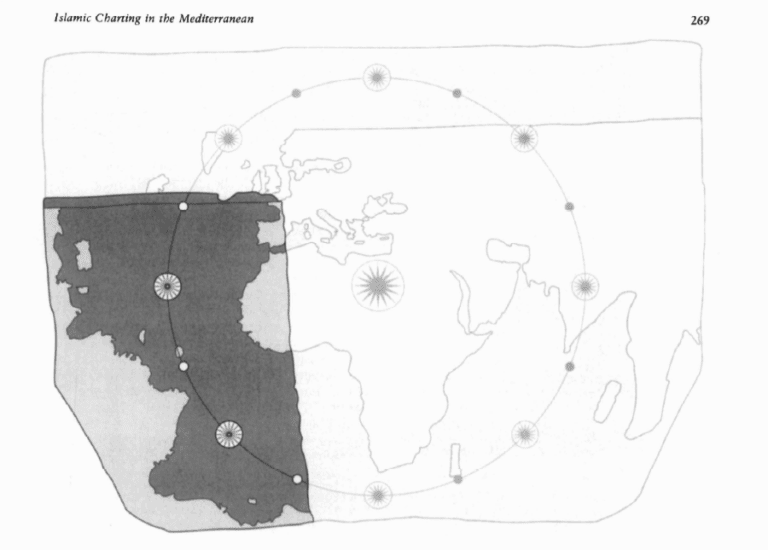

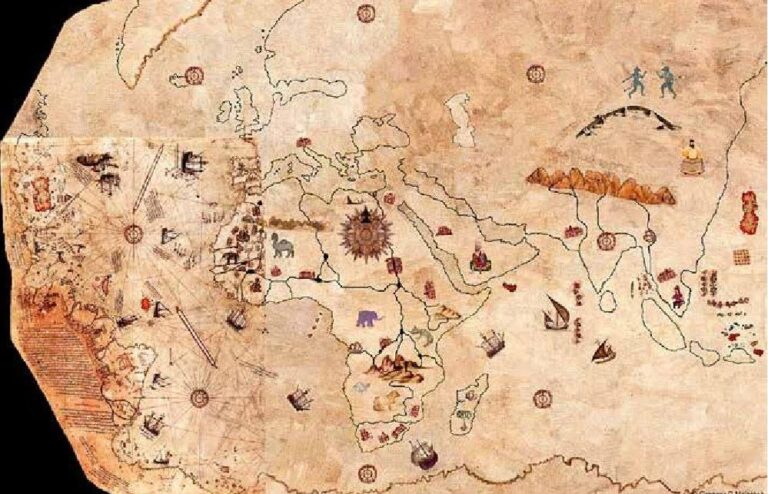

So, what would the complete map have looked like? A couple of scholars have had a crack at portraying the conjectural extent of it. Firstly, lets look at Gregory C. McIntosh’s colourful hypothetical reconstruction of the complete Piri Reis World Map 1513.

Secondly, Svat Soucek contributed the chapter ‘Islamic Charting in the Mediterranean’ to the seminal work edited by J. B. Harley and David Woodward, The History of Cartography.

His reconstruction shows Piri Reis’ knowledge and map finishing with Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, which does equate to the Portuguese knowledge that would have been available to him at that time.

Both reconstructions are, of course, conjectural; unless a long-lost copy, or even (please) the original somehow are rediscovered, we will never know what we are missing. It is a shame that Piri Reis’ work–and life–were unappreciated by the sultans that he dedicated his working life to, and it is only through recent research by scholars like McIntosh and Soucek that we have a clearer understanding of Piri Reis’ unique contribution to cartography.

As McIntosh so aptly puts it,

The Piri Reis map is a distinguished work of cartographic science, an important historical artifact, and one of the world’s great multicultural and intercultural unions of art and science. Piri Reis himself stands as an exceptional individual straddling the geographical and cultural borderlands between East and West, the Medieval and the Renaissance, and the Old and the New.