One of the pioneering ships that led the early Portuguese Indies fleets was a nao, or carrack named Flor de la Mar (Flower of the Sea). The Flor has become the stuff of legends due to her last, fateful voyage where she went down off the Sumatra coast loaded with looted treasure from newly-captured Malacca. Many maintain to this day that she is the richest of all the undiscovered shipwrecks across history’s pages and the world’s oceans.

Her story echoes the heady early days of Portuguese exploration and conquest, where intrepid mariner adventurers blazed a path across the oceans seeking spices and heathens to convert.

First to reach India was Vasco da Gama in 1498 with just four small ships. Overcoming considerable adversities, he returned to Portugal with cargos valuable enough to encourage further fleets to seek out the riches of the East. To equip such fleets however, more long-distance ships were needed, with larger cargo capacity than the smaller caravel exploration vessels. Originally broad, rounded-hull storeships, these early cargo carriers evolved into naos. Not as fast or weatherly as caravels, they could nevertheless haul several times the load and with higher freeboard were more difficult to board.

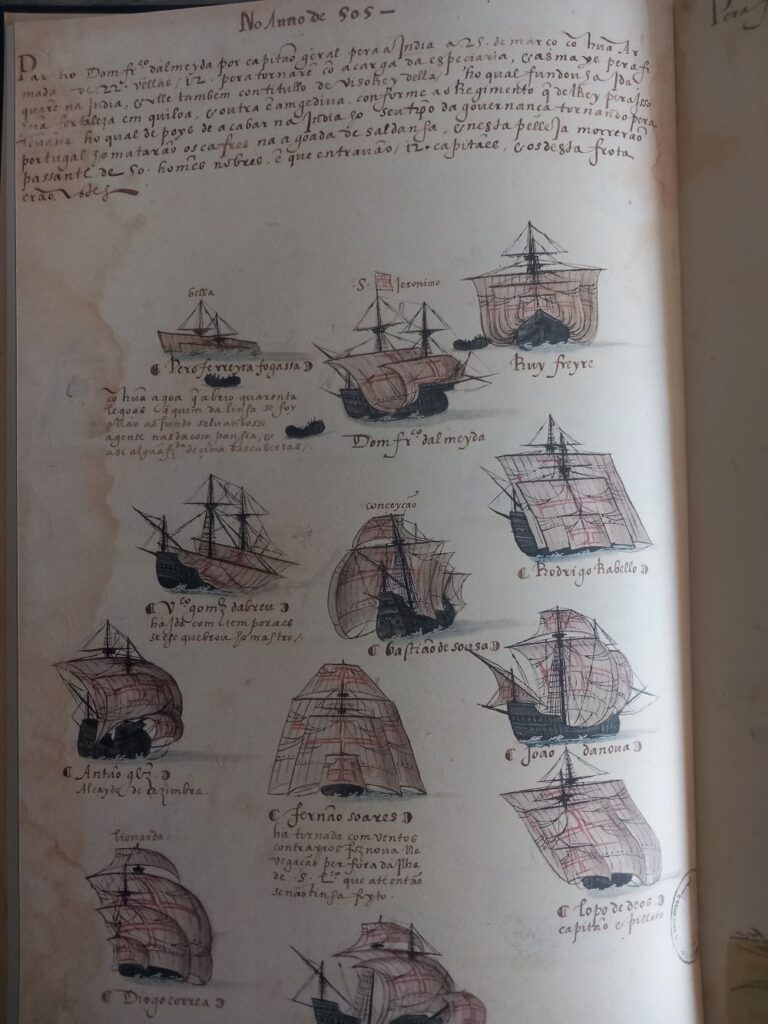

In 1500, thirteen ships set out for India but four were wrecked enroute, including that under Bartholemew Diaz; the first captain to round the Cape of Good Hope, lost without trace. Again, cargos of spices easily paid for the venture on their return to Portugal.

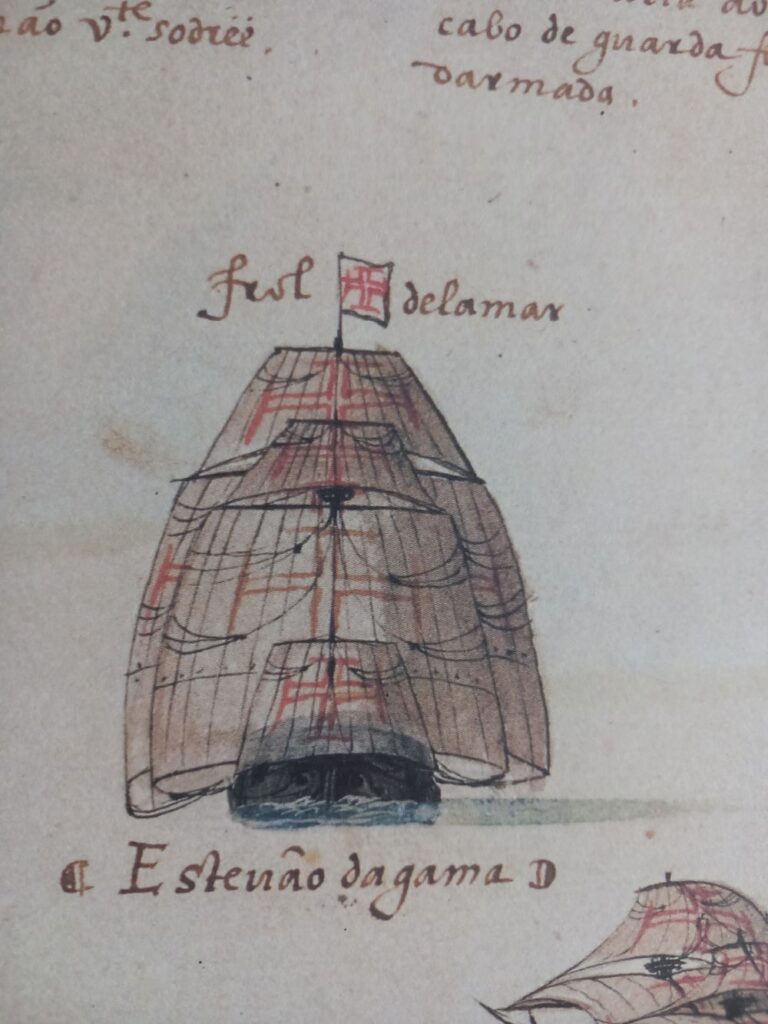

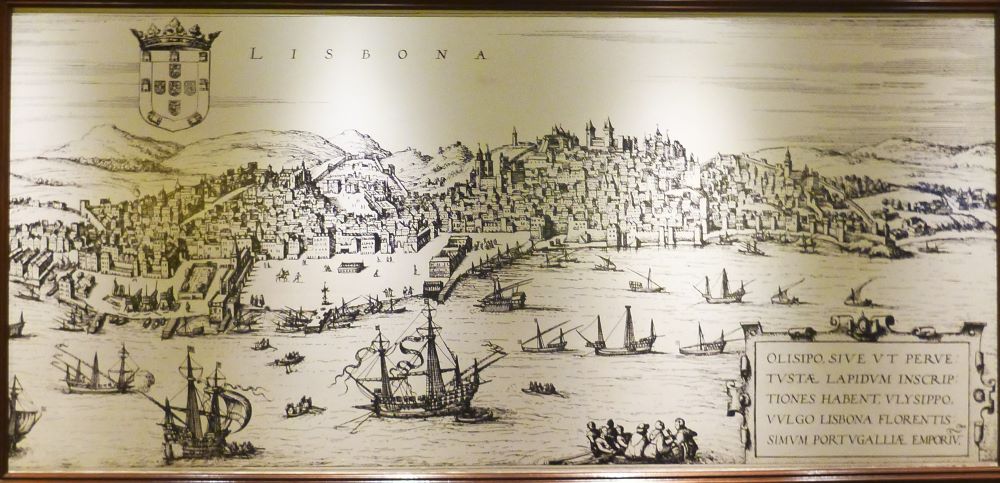

For the next fleet, the newly built large nao, Flor de la Mar (called Frol de la Mar, or ‘First of the Sea’ in early sources) was to lead one of the three squadrons totalling a mix of 20 naos and caravels. The fleet was led by nobleman Vasco da Gama with instructions to establish forts and bases along the East African and Indian coasts. Captain aboard the Flor was da Gama’s cousin, Estavao da Gama, who took her down Lisbon’s Tagus River in April 1502.

Vasco must have been impressed by the new Flor, because he took it as his flagship once it arrived in India.

The top image shows an artists rendition of a similar ship, the Santa Caterina do Monte Sinai about 1520, giving an indication of how the Flor de la Mar would have appeared.

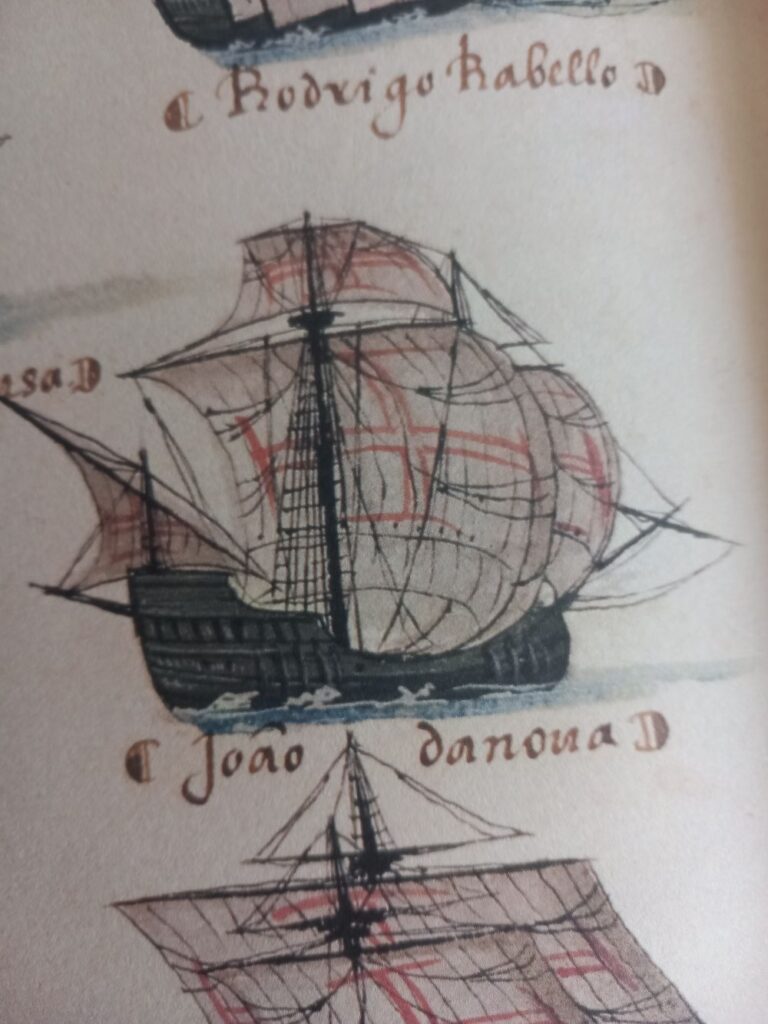

At a displacement of around 400 tons, it was his largest and probably most powerful ship. Her armament is not defined, and probably evolved over her career, but general references to weaponry on contemporary ships suggests she carried six big camelo’s on her gundeck firing 12-18 pound balls; two smaller (perhaps nine pounders) ones firing forward and aft; eight large swivel guns of around four pounds and ‘many’ smaller berco’s; breech-loaders firing two pounds of scattershot mounted around the ship’s rails.

She was fully rigged with three masts and a bowsprit, a billowing mainsail and topsail on the mainmast, a square foresail forward, and a triangular lateen on the mizzen which aided steerage. Tall fore and aft decks packed with small guns towered above most local vessels in the Indian Ocean, and the hull was deep and rounded for hauling large volumes. Her battery of main guns was low down amidships, manned by skilled gunners and of greater killing power than virtually any other broadsides the Portuguese encountered.

Alone under da Gama, the Flor successfully fought of a large Indian fleet that ambushed her in Calicut harbour, and returned with bulging holds to Portugal in 1503. When fully loaded she was difficult to manoeuvre, and had considerable trouble in the Mozambique Channel on her passage home. She left again for the gruelling 11,000 nautical mile journey to India in 1505 in a fleet of 22 ships. It was the last time she would see her homeland.

Back to India for another cargo run, she attempted to return to Portugal, but encountered similar problems to her previous passage, and was so delayed that she ran into the outgoing fleet of the next year, was unloaded, and turned around to head back to the battlefront again.

She fought in the Persian Gulf in Albuquerque’s squadron that took Muscat and Hormuz, then served as Almeida’s flagship when he demolished a combined Mamluk/Indian fleet off Diu, India in 1509. From there it was on to the seizure of Goa which would remain as the capital of Portuguese India until invaded by India in 1961.

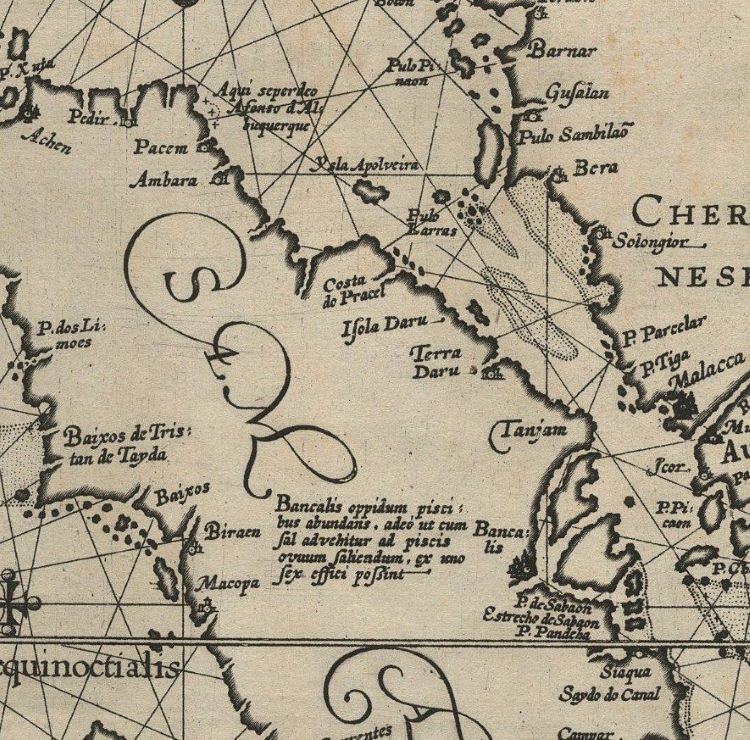

A Portuguese trading station had been established in Malacca, spice capital of the Indies, in 1509, but they were soon set upon by the Muslim rulers of the port and killed or captured. Word of this reached new governor of Portuguese India, Afonso Albuquerque, and as soon as the southwest monsoon blew in 1511, he steered for the Malacca Strait with a fleet of 16 ships and over 2000 men. He aimed to take the strongest, richest port in all of Asia.

Reports suggest that the departing governor had intended to take passage back to Portugal in the Flor–still only seven years old–and that he had it repaired for that journey, but he was overruled by Albuquerque who took the nao as his own flagship for the Malacca operation, suggesting it remained a capable ship.

The battle for Malacca was one of the hardest-fought battles the Portuguese engaged in, but in the end superior discipline, tactics and firepower led to victory over the forces of the sultan. At the time the Sultanate of Malacca was regarded as one of the wealthiest ports on earth. Portuguese chronicler Tome Pires described it around the time of the Flor’s demise:

There is no doubt that the affairs of Malacca are of great importance, and of much profit and great honour. It is a land that cannot depreciate, on account of its position and must always grow. No trading port as large as Malacca is known, nor any where they deal in such fine and highly prized merchandise…It is at the end of the monsoons, where you find what you want, and sometimes more than you are looking for.

The ruling sultans profited immensely from trade. Firstly, they exacted a percentage ranging from 2-6% on all imports from east and west. Secondly, they secured additional ‘gifts’ on all incoming shiploads. Thirdly, they financed ships and voyages themselves on the most profitable trade routes, and provided finance to others for a share of profits. Fourth, a proportion of the weight of all incoming foodstuffs and goods was required as a donation. Fifth, the sultan received substantial tribute from vassal states, and official gifts from rulers ranging from Hormuz to Canton. Finally, various taxes were levied on local businesses, like warehousing, money changing, stevedoring and provisioning.

The Portuguese estimated the sultan’s wealth at the time the city fell to Albuquerque at 140 quintals of gold (about nine tons), and we can assume they counted it to arrive at that figure. Additionally, there was hordes of precious stones, merchandise, spices and a huge array of impressive gifts of tribute, built up over a century of intimidating vassals.

Once Malacca was in his hands, Albuquerque dealt with re-establishing the port to operation and defending it from the inevitable counterattack. A fortress was commenced, local officials appointed to manage the administration, a small fleet of galleys constructed, envoys dispatched, and reassurance provided to the essential merchants that it was business as usual.

With all this done and Malacca safe, he needed to urgently return to India to recapture Goa, which had been lost in his absence. When the winds of the northeast monsoon arrived late in 1511, he set of from Malacca in the Flor, accompanied by three other ships, making for India.

At this point, eyewitness reports get murky and contradictory, and these have been built on by subsequent myths, suppositions and erroneous interpretations. Most agree that after a number of days in the Strait, a storm caused the Flor to be wrecked on the coast of the Aru Kingdom. Opinions vary on whether this occurred in late 1511 or early 1512 and, critically where exactly it occurred.

Generally, it is assumed the ship hit a reef just offshore in the area off what used to be called Tamiang (or Timia) Point, south of modern Langsa. Winds in that late year season tend to be onshore, discounting the likelihood of a predominantly southeasterly ‘sumatra,’ storm–common on that coast–as the culprit. Heavily loaded and with a fresh onshore wind, the notoriously un-manoeuvrable nao probably found herself unable to stand off the coast into the wind, and it was the dark of the night as well.

Albuquerque mentions that only himself and a few survivors escaped during the storm on a makeshift raft, and that the rest of the crew and all the treasure was lost. Other reports indicate that some of the Flor’s consorts carried out rescues and salvage with the dawn, and infer that apart from the bulk of the copper coinage, much of the nao’s load was recovered. To complicate the picture further, Portuguese survivors from the vessel are said to have landed in Pase (Pacem to the Portuguese) 90 miles further up the coast.

The major consideration though is that the Kingdom of Aru was renowned as home to the worst pirates of the entire corsair-ridden Sumatra coast, and they are unlikely to have ignored a wrecked galleon sitting just off their beach. Probably after eating any survivors. Indeed, Albuquerque claims that a group of cannibals from Aru were employed by the sultan in pre-Portuguese Malacca to consume criminals when the death sentence was imposed.

So, while many modern treasure hunters still scour the north Sumatra coastline five centuries on, hopeful of fame and fortune, the glum reality is that everything of value has already most likely been long purloined or is inaccessible.

But it’s a great story anyway.