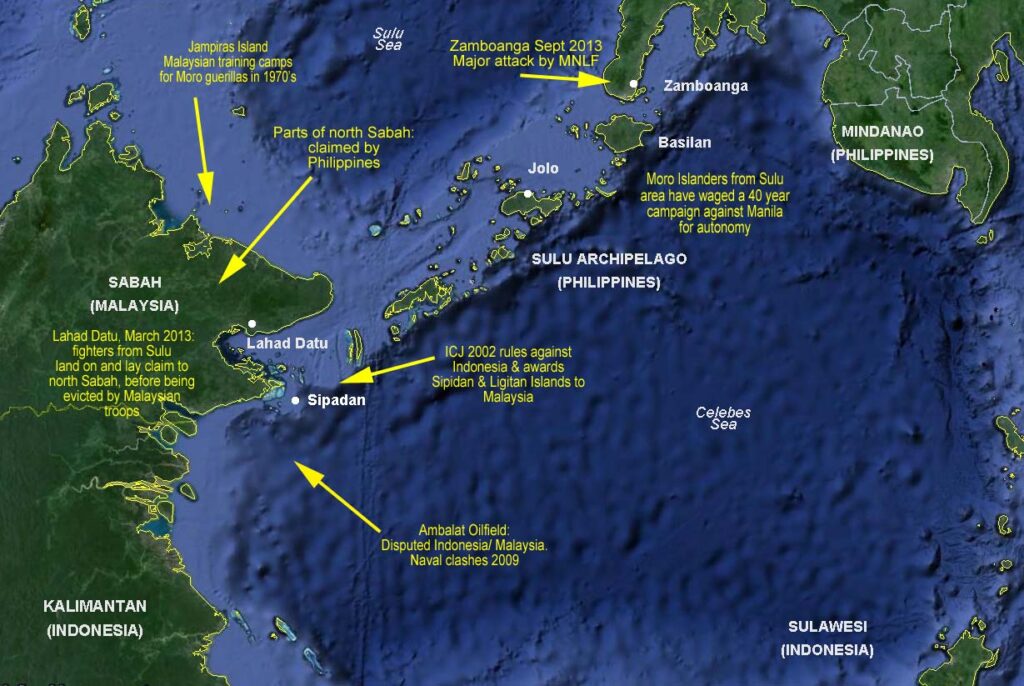

In February 2013, several hundred armed Filipino nationals landed in the Malaysian state of Sabah, on the island of Borneo, seeking to assert their claimed, historical right to a part of that state’s sovereignty. Clashes with Malaysian security forces ensued, leading to dozens of deaths and the eventual deployment of seven army battalions and even F-18 Hornets to defeat the insurgents in what became known as the Lahad Datu Incident. How did it all come to this?

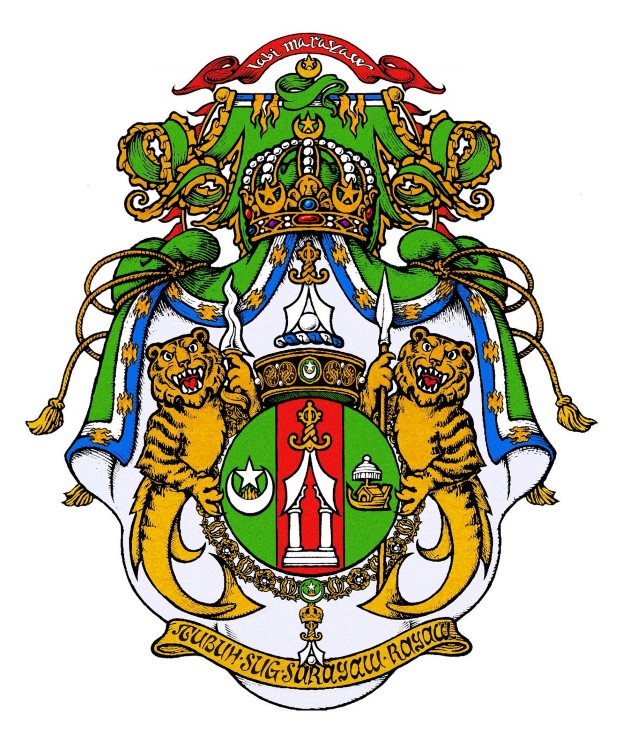

To answer this question, we have to go back in time and take a closer look at the Sulu Sultanate and its Moro (Moor, or Islamic) people.

Pre-colonial glimpses of the Sulu archipelago are provided by Ming Chinese accounts which describe a Hindu entrepot paying tribute to the Chinese emperor and famed for its pearls and pirates. At times it formed part of the Java-based Majapahit Empire, and at others was in conflict with it.

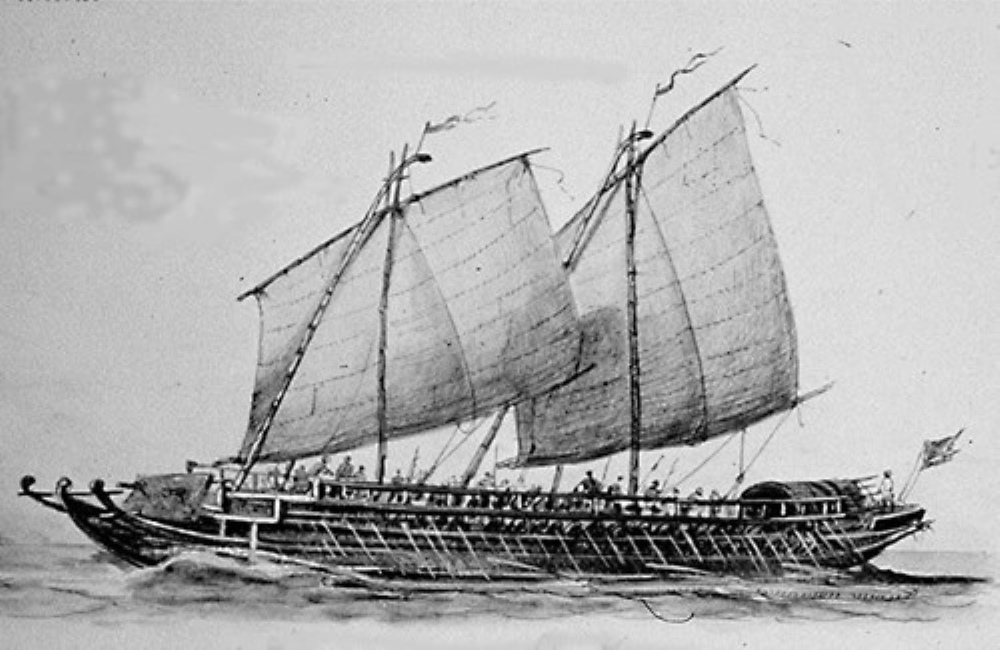

Islam began to arrive in Southeast Asia via Persian, Arab and Indian traders in the thirteenth century, and by the early fifteenth, Sulu became a sultanate, based at Jolo, one of the principal islands of the archipelago. As a maritime sultanate, it vied for control of the wider region, regularly coming into conflict with neighbouring sultanates at Brunei, Ternate and Tidore, fighting for influence throughout Palawan, Mindanao, the Moluccas and northern Borneo. Sulu’s warriors tended to be sea raiders, not farmers.

The arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century led to an extended series of clashes with the Moro’s of the Sulu region who sat astride resupply routes between the new Spanish capital at Manila and the Spice Islands in today’s Indonesian Maluku provinces. Gradual enlargement of areas under Spanish control in the southern Philippine islands were simply an invitation for the Moros to turn their raiding focus northwards. But the Spanish were not about to tolerate that.

Kicking it all off, Spanish Captain Don Estevan Rodriguez de Figueroa was dispatched to Jolo in 1578 to lay down the law. The sultan was to submit to the Spanish crown, pay an annual tribute of pearls, hand over a prince as a hostage, surrender all offensive weapons and watercraft, cease practising Islam, and facilitate Christian missionaries. Unsurprisingly rebutted on all clauses, the captain landed, defeated the Jolo warriors, stormed the fort and put all to the sword, taking his pearl tribute and returning to Manila.

It took the Sulu fighters some years to recover from this, but by 1600, they were raiding and pillaging again through the newly Christianised islands to their north, using squadrons of their korakora derivative. Such depredations invited frequent Spanish retribution, but again and again the Moro’s bounced back from Spanish reprisals. The cycle of violence for the next 250 years was the same; Moro raids through the central Philippine islands, brutal Spanish punitive expeditions in response, ineffectual peace treaties followed by renewed plunder and pillaging.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the British, French, Germans and Dutch all entertained ideas of colonising the Sulu Archipelago; the East India Company even maintained a base there (Balambangan Island 1763-1775 & 1803-1805), but all departed quickly from the scene, happy to leave the Spanish the interminable job of pacifying the Moro’s.

At its greatest extent in the mid-nineteenth century, the Sulu Sultanate controlled all the islands between Mindanao and Borneo and substantial coastal areas of what is now Sabah state. Not until 1878 was Spain able to establish a permanent garrison on Jolo and grant a measure of autonomy, which stilled the carnage somewhat until the US arrived.

The Americans took possession of the Philippines as a colony following their 1898 victory over Spain, but immediately faced uprisings from both the Christian and Muslim populations. The Moro’s of Sulu were the most obstinate and refused to submit or be disarmed, resisting external control with their customary vigour. Interestingly, the famous US handgun, the Colt 45, was initially developed to provide more stopping power against enraged Moro attackers during this campaign. Combining brutal force with effective administration, the US eventually pacified the rebels, during the Moro Wars, but took over a decade to do so.

The Japanese, occupying the islands in WWII also suffered at the hands of local guerrillas. After 1946, it was the turn of the newly independent Philippine government to try to assert control over the Moros, which they have struggled for decades to achieve. For large parts of the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, the Sulu Islands were a no-go zone. Some success has been achieved by conciliation, autonomy and investment in the Sulu area in recent years, though incidents like at Zamboanga 2013, Mamasapano 2015 and the full-scale siege of Marawi in 2017–where a thousand militants were killed in the five month battle are indicative of the problems going forward.

One of the complications of the relationship between neighbours Malaysia and the Philippines has been the issue of the Sultanate of Sulu’s claims on Sabah. These claims are based on an 1878 Treaty signed with the legal predecessors of the Malaysian state, either ‘ceding’ (the Malaysian interpretation) or ‘leasing’ (the Sultanate’s interpretation) areas of north Borneo for a perpetual annual payment of 5000 Malaysian dollars. While recently discontinued, this payment had been made, every year, for over a century, giving the claim at least a veneer of authenticity. And the presence of modest petroleum reserves in the disputed areas adds spice to the potential Sabah prize.

The Philippine state, as successor to the Sultanate of Sulu, has always maintained its entitlement to parts of Sabah, but rarely seriously pressed the issue with Malaysia. There was a time however, during the rule of President Marcos in 1968 when Moro guerillas were supposedly trained at Corregidor to infiltrate and destabilise Sabah in an effort to further Manilla’s claim. This ultimately futile operation ended with the Jabidah massacre, where Moro recruits were purportedly gunned down by Philippine army troops when they mutinied. This massacre was one of the main triggers that intensified armed Moro resistance to the Philippine state. A number of Moro groups opposing integration with the Philippines sprung up, including the Moro National Liberation Front, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and the notorious kidnap-for-ransom group, Abu Sayyaf.

Perhaps in response to the Philippine attempt at infiltration, Malaysia supposedly decided to try the same technique in reverse. Moro guerillas were trained and armed at Jampiras Island in the 1970’s with the idea of fomenting anti-Manilla rebellion among their co-religionists, the Moros of Sulu. But this later backfired on Malysia, when the large community (c. 800,000) of mostly-Moro Filipino legal and illegal immigrants in Sabah came under pressure from authorities and locals due to their suspected successionist tendencies. The armed Moro groups then began to oppose Malaysian authorities in Sabah to protect their brethren in the area. The irony of the Moros now threatening guerrilla war against them in Sabah was surely not lost on the Malaysians.

Small scale criminal activities, robbery and kidnapping escalated over the years along the Sabah coast into larger and more deadly clashes, culminating in the Lahad Datu battle of 2013. This began when one (among several) claimant to the long-vacant throne of the Sultanate of Sulu, Jamalul Kiram III, ordered the ‘Royal Forces of the Sultanate of Sulu and North Borneo’ to Sabah to assert his longstanding prerogative.

Malaysian police blockaded the militants and issued an ultimatum to withdraw, but when a police patrol was ambushed and two officers killed, tensions rose significantly. Further groups of militants were landed and a second clash followed where a Malaysian superintendent and four officers were killed along with several militants during another ambush. Malaysia ordered its military into action for the first time, and following an airstrike by RMAF Hornets, a salvo of MRLS and a mortar barrage, the insurgents positions were stormed, ultimately leaving around 60 militants dead. Following Lahad Datu, Malaysia suspended ongoing payments to the heirs of the sultanate.

Jamalul, the instigator of the whole mess, escaped the security cordon and died later that year at Sulu, but his followers maintain their claim to Sabah. The reinvigoration of the dormant claim has given the Muslim Moro’s and the mainly Christian Filipino population some common ground. For once they are united with a mutual cause.

There are however, other Moro claimants to the throne of the old Sultanate. And these decided on a very different strategy. Firstly, in February 2022, these claimants won a spectacular international arbitration victory against Malaysia amounting to $USD15 billion for breach of the 1878 Treaty. In July 2022, bailiffs in Luxemburg acting on behalf of the last sultan’s heirs served asset seizure notices and account freezing applications at subsidiaries of Petronas, the Malaysian state-owned energy giant that brings in 15% of government expenditure.

Seeing the claimants bankrolled by a savvy UK venture capital fund and with a court order applying 10% damages per year to the claim, Malaysia is naturally very alarmed, and has strenuously appealed the decision. Subsequent proceedings could go either way, but it is certainly going to be an interesting and very unique case to follow in future years.

Meanwhile, Indonesia, which itself tried to destabilise Sabah during the Confrontation of the 1960s, was peeved to lose a similar arbitration case against Malaysia over ownership of the resort islands of Sipidan and Ligitan, off the Borneo coast in 2002. The nearby Ambalat oilfields are also claimed by both countries and the scene of minor naval clashes in 2009.

Its not as contested as the nearby South China Sea, but North Borneo and the Sulu Islands are likely to remain in the news for years to come.