Fought over several months in 1511, the Battle of Malacca pitted the incumbent Malay sultan, Mahmood Shah, against the attacking Portuguese under Afonso Albuquerque.

Control of the most famous emporium of the East was up for grabs. At the time, Malacca was a fabulously wealthy entrepot trans-shipping trade goods between the Indian Ocean, the islands of the modern Indonesian archipelago and the China Seas. Tome Pires, a Portuguese apothecary based at Malacca wrote in 1515:

No trading port as large as Malacca is known, nor any where they deal in such fine and highly prized merchandise.

The sultan clipped a fee off every load of merchandise that passed through the port; Indian cloth and ivory, Chinese silk and porcelain, nutmeg and mace from Banda, cloves from the Moluccas, pepper, camphor and gold from Sumatra, aromatics, precious stones, gems, pearls, hardwood, tin and a hundred other products. And as the sultanate had been operating for a century, it was ridiculously wealthy, though the sultan not overly energetic or benevolent as a ruler.

It would be a battle between two very different opponents. On the one hand, the sultan was able to mass 20,000 men with war elephants, but his warriors were not trained for formation warfare, and lacked discipline and battle experience. His forces fought with shields and swords, also using lances, archery and blowpipes with poisoned darts. They did have quite a number of cannon, small and large, from foundries in India, Siam and Pegu, but they lacked trained gunners, an understanding of how to effectively use such weapons and they played no significant part in the battle. They had no naval vessels capable of taking on the Portuguese ships and there were no modern fortifications.

The Portuguese on the other hand fielded just 800 men, but most had fought their way from Morocco all the way to India, and were used to being outnumbered, though rarely outgunned. They arrived in 18 heavily-armed ships; a mix of larger carracks, and smaller caravels, all fitted with heavy anti-ship cannons and numerous smaller breech-loading swivel guns. All aboard were experienced in combat, particularly amphibious operations and operated in ‘battalions’ under their officers. They fought in full or partial armour, providing some protection against edged weapons, and were armed with swords, crossbows and early muskets, though the considerable difficulties in reloading these limited their use after the first discharge of a clash. Their shipboard cannons were devastating when directed at land targets and concentrations of troops. The firepower they provided was crucial in the coming battle.

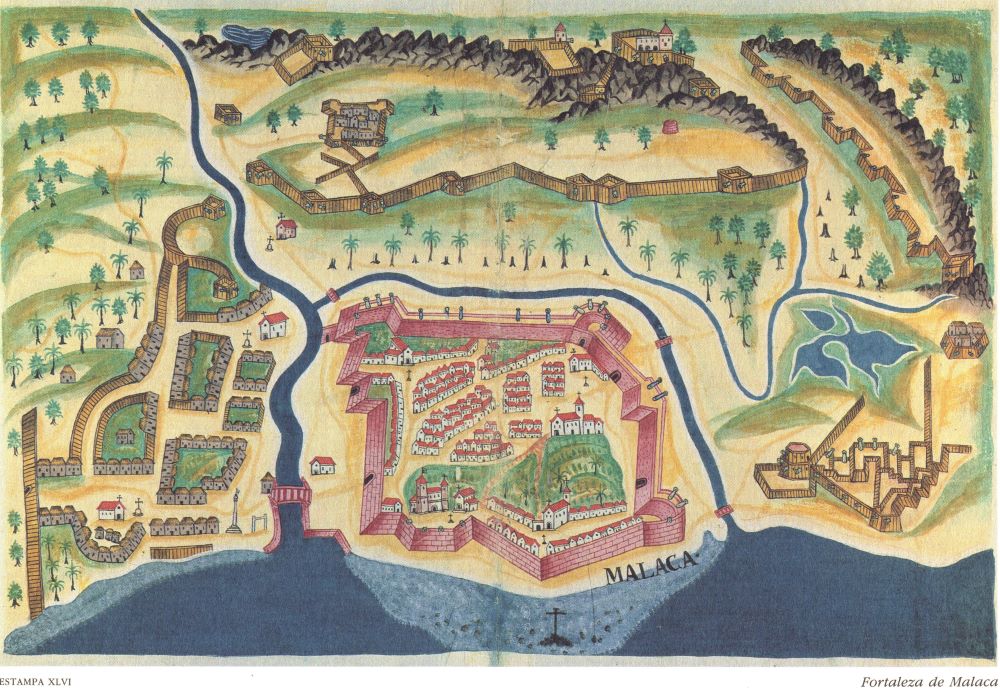

Malacca itself sat astride a small river mouth with the merchant’s villages on the northern bank with the mosque and sultan’s palace on a small hill on the southern bank. Larger ships anchored just offshore in the protected waters of the Malacca Strait. A timber bridge, with a raised central span to allow smallcraft to enter the river, linked the two banks close to the river’s mouth. It was control of this bridge that would be the key to victory.

Portuguese chronicler Godinho Eredia writing in 1613, described Malay warfare:

…they only make use of attacks and sallies in mass formation: their sole plan is to construct an ambush in the narrow paths and woods and thickets, and then make an attack with a body of armed men: whenever they draw themselves up for battle, they acquit themselves badly and usually suffer heavy losses.

However, the Portuguese were no icons of military prowess themselves, as C.R. Boxer notes:

This lack of discipline and military training was allied to an overweening self-confidence which rendered the Portuguese notoriously careless and negligent at critical times and places where great care and vigilance were necessary.

It had been a busy couple of years for Albuquerque, Governor of India, and responsible for Portugal’s budding empire from Mozambique to China. In January 1510, he was wounded in an unsuccessful attack on Calicut, India. He was then preparing to strike a Mameluke fleet assembling at Suez in the Red Sea when Indian pirate Timoja convinced him to capture Goa, an ideal base for Portugal’s Indian operations. The city was taken in February but a strong counterattack drove Albuquerque’s men back to their ships, before reinforcements were gathered and in November a second, larger attack on Goa was mounted. This bitter battle was eventually successful, but it took Albuquerque some months to put the defences in order for further anticipated attacks by the displaced Muslim ruler. Goa subdued, he had plans to establish bases at Hormuz, Aden and Malacca to control the whole Indian Ocean. He would start with Malacca.

As soon as the winds allowed, Albuquerque sailed east. An earlier Portuguese trade mission to Malacca had been imprisoned there since 1509, and in July, his fleet stood off the port, demanded their release, payment of compensation and permission to build a fort. The sultan procrastinated, unused to Albuquerque’s direct style of negotiating. The Muslim shipping off the port was burnt, but still the sultan failed to grasp the danger of his situation. Probably nothing would have saved him at this stage anyway.

Eager for the glory of another stage in the Christian war against the infidels, the Portuguese attacked at dawn on St James Day, 25 July. One force landed north and one south of the river, and both turned to attack the heavily defended bridge. On the southern bank, the Portuguese overran the mosque and one end of the bridge in brutal hand-to-hand combat against warriors armed with lances, swords and shields. The sultan recognised the danger; his forces were now split in two. The bridge had to be retaken. He led the first counterattack atop a war elephant, but this attack was driven back by Portuguese lances.

Albuquerque, on the north bank, first repelled an attack from a large force attacking down the river and then subdued the defenders barricaded on the bridge, though suffering heavy casualties to arrows and darts. By then it was 2 pm, very hot, his men were exhausted after eight hours of fierce combat, he had seventy wounded, and not enough supplies or ammunition to last through the expected counterattacks during the night. Painfully, he withdrew back to the ships, taking fifty captured cannon with him.

As soon as the Portuguese departed, the sultan’s forces re-occupied the bridge, and set about improving the barricades at either bank, including fitting more cannon. It would now be an even tougher nut to crack.

Albuquerque could have bombarded the town with his ship’s guns, but this would have destroyed the port and warehousing facilities, as well as alienating the merchants he needed to manage ongoing trade. After consulting with his officers, it was decided to attack the bridge once more.

This time, a large junk was converted into a floating fortress; heavily armed, fitted with heavy barricades for protection, and loaded with ample supplies. Its high freeboard would allow the attackers to dominate the defenders on the bridge. Breech loading swivel guns with a two-inch bore were mounted on the ship’s rails firing scattershot; these could be quickly reloaded with several prepared chambers, giving an impressive rate of firepower.

All was ready to proceed, but the heavy junk grounded on shallows at the bar of the river and waited there stuck for several weeks, until mid-August when the tides were at flood. The defenders could see the preparations and floated fireships down the river in an effort to torch the junk, but these were repelled. Their failure over the intervening time to use their cannon to destroy the junk indicated their lack of skill with ordnance and was to have fatal consequences for the sultanate.

When the junk refloated, she came up on the bridge and swivel guns swept it clear of defenders. The Portuguese also used grenades from the crows-nest and muskets and javelins from the deck. Again, forces landed north and south to subdue the sultan’s troops, and quickly took both sides of the crossing. The sultan again countered with war elephants from the direction of the mosque, but were once more repelled.

Albuquerque demonstrated impressive control over his forces, keeping them concentrated around the bridge to defeat counterattacks, when lesser leaders would have been troubled to prevent a wild sack of pillage and looting. The stockades were rebuilt and armed with the supplies carried aboard the junk, and there was water and provisions.

Now they had control of the bridge, a number of gun barges were floated up the river and bombarded the remaining defences for ten days. The sultan and his remaining warriors had cleared out long before. The city now belonged to Portugal.

Albuquerque energetically organised the new administration of the port and city, the construction of a church, and the building of a fortress to defend against the expected attempts to retake the jewel in the sultan’s crown. Twelve galleys were laid down to form the city’s defensive squadron, cannon landed for the new ramparts and a garrison left to man the fortress.

Hormuz and Aden were beckoning, and so Albuquerque loaded the sultans spoils–and his harem–aboard the flagship and set out to return to Goa. His ship, the Flor de la Mar went down with all the treasure in a squall off the Sumatra coast, the governor one of the few survivors. The wreck remains the richest undiscovered shipwreck on the planet.

The sultan stayed further up the river for months, wondering why the Portuguese stayed on and on. A Malay prince would have pillaged the place and left. He reformed his sultanate in Johore, and made several attempts to regain Malacca–all unsuccessful. Portugal held Malacca for just 130 years before losing it to the Dutch after an extended siege, but by then Malacca had long lost its lustre.